|

Blogを斬る,おまけ

2022.03.21

小野沢あかねさんによるラムザイヤー論文への反論(英文)がアップされました。 を斬る

2022.03.26 反駁部分の記述を一部改正

|

|

引用元URL → https://fightforjustice.info/?p=5649 ( 魚拓 )

このページは、webサイト『Fight for Justice 日本軍「慰安婦」――忘却への抵抗・未来の責任』 が開

設された2013年08月01日時点で存在しなかったページです。

いつ追加されたのか?は、

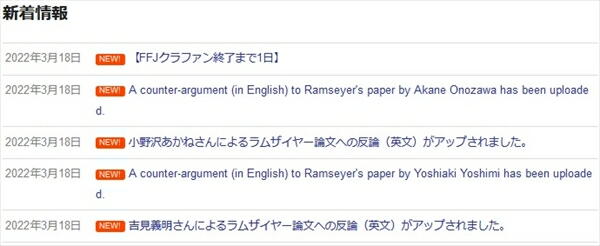

より、皇紀2682年03月18日だそうです。

では、いざ参る。

小野沢あかねさん(立教大学教授、近代日本公娼制研究)によるラムザイヤー批判論文(英文)が3

月15日、ジャパンフォーカスに掲載されました。ご参照ください。拡散歓迎します。

Problems of J. Mark Ramseyer’s “Contracting for Sex in the Pacific War”: On Japan’s Licensed

Prostitution Contract System

J・マーク・ラムザイヤーの「太平洋戦争におけるセックス契約」の問題点:日本の売春契約制度につ

いて

By Onozawa Akane

小野沢茜著

Translation by Miho Matsugu

松宮美穂訳

https://apjjf.org/2022/6/Akane-Matsugu.html

Problems of J. Mark Ramseyer’s “Contracting for Sex in the Pacific War”: On Japan’s Licensed

Prostitution Contract System

J・マーク・ラムザイヤーの「太平洋戦争におけるセックス契約」の問題点:日本の売春契約制度につ

いて

Onozawa Akane

小野沢茜

Translation by Miho Matsugu

松宮美穂訳

March 15, 2022

2022年3月15日

Volume 20 | Issue 6 | Number 2

20巻|第6号| 2番

Article ID 5689

記事ID5689

Abstract: This article offers a critical assessment of J. Mark Ramseyer's analysis of the wartime

Japanese military "comfort women" system, "Contracting for sex in the Pacific War", Closely

examining the Japanese sources that Ramseyer cites, it finds the article flawed in distorting the

evidence and in confusing the prewar system of prostitution and the wartime system.

要約:この記事は、戦時中の日本軍の「慰安婦」システム、「太平洋戦争でのセックスのための契約」

に関するJ.マーク・ラムザイヤーの分析の批判的な評価を提供します。証拠を歪め、戦前の売春制度

と戦時制度を混同している。

1. Introduction

1.はじめに

1-1. Problems with the Ramseyer Article

1-1。ラムザイヤーの記事の問題

In his article "Contracting for Sex in the Pacific War", J. Mark Ramseyer lays out an

interpretation of Japanese military "comfort women" that is contrary to the facts.1 Ramseyer's

argument is that the Korean women who became "comfort women" were their own agents on the

contracts: they negotiated with the owners of the "comfort stations", became "comfort women" by

mutual consent, and earned a large amount of money. Although he concedes that among Korean "

comfort women", there were some who were deceived into working at the comfort stations, he

argues that the brokers were Koreans and the comfort stations who employed and managed the

women were privately owned and were only used, and not controlled, by the Japanese military.

J・マーク・ラムザイヤーは、彼の記事 「太平洋戦争における慰安婦契約」 の中で、事実に反する日

本軍の「慰安婦」の解釈を示しています。1 ラムザイヤーの主張は、「慰安婦」 になった韓国人女性は

契約上の彼ら自身の代理人:彼らは 「慰安婦」 の所有者と交渉し、相互の同意によって 「慰安婦」 に

なり、多額のお金を稼いだ。彼は韓国の「慰安婦」の中には慰安婦で働くことに騙された人もいたと認

めているが、ブローカーは韓国人であり、女性を雇用し管理した慰安婦は私有であり、使用されただけ

であると主張している。 日本軍によって支配されていない。

There has already been a large amount of international criticism of Ramseyer's argument about

Japanese military "comfort women",showing his inappropriate manipulation of historical documents.2

In this article, however, I want to show that the argument about Japanese military "comfort women

" that I described above is not the only problem with the Ramseyer article. In it, Ramseyer deploys

his claims not only about the issue of "comfort women" but also about Japan's prewar prostitution

system.

They are both deeply related to historical revisionism on the issue of "comfort women".

The following is what I find problematic in Ramseyer’s assertions.

ラムザイアーの日本軍の 「慰安婦」 についての議論は、歴史的文書の不適切な操作を示しており、

すでに多くの国際的な批判があります2。

しかし、この記事では、日本軍の 「慰安婦」 についての議論を示したいと思います。

ラムザイアーの記事の問題は、上記で説明したことだけではありません。

その中で、ラムザイヤーは 「慰安婦」 の問題だけでなく、日本の戦前の売春制度についても彼の主

張を展開している。

どちらも 「慰安婦」 問題の歴史修正主義と深く関わっています。

以下は、ラムザイヤーの主張で私が問題だと思うことです。

The first problem is Ramseyers insistence that under the prewar Japanese prostitution system,

licensed prostitutes (shogi) exercised agency when they entered into what he says was a mutually

agreed-upon contract. "The women forced recruiters" to put their money behind promises in the

contract, he wrote, by making them pay "each prostitute a large fraction of her earnings upfront",

and cap "the number of years she would have to work".3

第一の問題は、戦前の日本の売春制度の下で、認可された売春婦(将棋)が彼の言うことを締結し

たときに代理人を行使したというラムゼイヤーズの主張は、相互に合意された契約であった。

「 女性はリクルーターに彼らのお金を契約の約束の後ろに置くことを強制した 」 と彼は書いた。

"In cities like Tokyo, they could easily leave their brothels", he writes.4

"In practice, the prostitutes repaid their loans in about three years and quit" 5 and "She would

have repaid her initial loan of 1,200 yen in about 3 years".6

As these examples illustrate, Ramseyer claims not only that the licensed prostitutes were able to

quit any time they wanted but also that their terms of work were short, their incomes were high,

and they were able to easily pay back the loans they had received when they started working.

「 東京のような都市では、売春宿を簡単に離れることができた 」 と彼は書いている。4

「 実際には、売春婦は約3年でローンを返済して辞めた 」 5 そして 「 彼女は約3年で1200円の最初

のローンを返済したであろう 」 6。

これらの例が示すように、ラムザイヤーは、認可された売春婦はいつでも辞めることができただけで

なく、彼らの仕事の条件が短く、収入が高く、受け取ったローンを簡単に返済することができたと主張し

ています 彼らは働き始めました。

The second problem is Ramseyer's claim that the contracts used between "comfort women" and

the owners of comfort stations were the same as those used for karayuki-san, Japanese women

who were sold into prostitution in Southeast Asia and other areas.7

As he writes, "the comfort stations hired their prostitutes on contracts that resembled those

used by the Japanese licensed brothels on some dimensions.8

In this way, Ramseyer terms "comfort women" as "prostitutes,” and equates their contracts to

those under which licensed brothels employed licensed prostitutes. In other words, his logic is that

since "comfort women" were almost the same as licensed prostitutes, they must be working under

the same conditions, including being able to exercise their agency in entering into contracts, to quit

easily, and to pay back their loans since their incomes were high.

第二の問題は、「慰安婦」 と慰安所の所有者との間で結ばれた契約は、東南アジアなどで売春に売

られた日本人女性のからゆきさんと同じであるというラムザイヤーの主張である。

彼が書いているように、「 慰安所は、いくつかの面で日本の売春宿で使用されているものに似た契約

で売春婦を雇った。」 8

このように、ラムザイヤーは 「慰安婦」 を 「売春婦」 と呼び、その契約を、売春宿が売春婦を雇った

契約と同一視している。

言い換えれば、「慰安婦」 は売春婦とほぼ同じだったので、彼らは、契約を結ぶ際に代理店を行使す

ることができ、簡単に辞めることができ、収入が高かったのでローンを返済することができるなど、同じ

条件で働いている必要があります。

Let me explain how these claims are contrary to the facts and how Ramseyer justifies such false

claims.

これらの主張が事実に反していることと、ラムザイヤーがそのような誤った主張を正当化する方法を

説明しましょう。

First, the contracts between licensed prostitutes and brothel owners were not based on an even

relationship. The contracts were de facto human trafficking given the strong power relationship

between women who could do nothing but become prostitutes, and the brothel owners. Such a

power relationship also existed between licensed prostitutes and their parents because they were

sold by their parents.

Because the status of women in the family system in modern Japan was low,9 it was believed to

be unavoidable for parents to sell their daughters when their ie or "household" faced a crisis. There

are numerous personal notes written by former licensed prostitutes and geisha, as well as interviews

with them. It is clear from these that their parents sold them to the owners of brothels and geisha

houses.10

As I will explain later, licensed prostitutes' incomes were so small that they were hardly able to

pay back their debts and it was extremely difficult to quit at will.

第一に、認可された売春婦と売春宿の所有者との間の契約は、平等な関係に基づいていませんでし

た。

売春宿にならざるを得ない女性と売春宿の所有者との間に強い権力関係があることを考えると、契

約は事実上の人身売買でした。

そのような権力関係は、彼らが彼らの両親によって売られたので、認可された売春婦と彼らの両親

の間にも存在しました。

現代日本の家族制度における女性の地位は低いため 9、彼らのすなわち 「世帯」 が危機に直面し

たとき、両親が娘を売ることは避けられないと信じられていた。

元免許を持った売春婦や芸者が書いた個人的なメモや、彼らへのインタビューがたくさんあります。

これらのことから、両親が売春宿や芸者の家の所有者にそれらを売ったことは明らかです。10

後で説明するように、認可された売春婦の収入は非常に少なく、借金を返済することがほとんどでき

ず、辞めるのは非常に困難でした。 意のままに。

Secondly, the licensed prostitution system in prewar Japan was not the same as the wartime "

comfort women" system.

The licensed prostitution system in modern Japan and its colonies and the "comfort women"

system do have a commonality in that both were systems of sexual slavery.

Yet, the "comfort women" system was different from the licensed prostitution system mostly

because it was the Japanese military that established the comfort stations and recruited "comfort

women".

They were different also because, while many of the Japanese "comfort women" were licensed

prostitutes, geisha and shakufu (barmaids) who were forced into the work, other women in Japan's

colonies and occupied areas who were forced to become "comfort women" had nothing to do with

prostitution and were recruited without contracts by the Japanese military or by contractors

instructed by the military, using violence, deceit and human trafficking.

These facts have been proven not only by personal testimony but also with scholarship based on

a huge amount of historical records including official documents.11

第二に、戦前の日本で認可された売春制度は、戦時中の 「慰安婦」 制度と同じではありませんでし

た。

現代日本とその植民地で認可された売春制度と 「慰安婦」 制度は、どちらも性的奴隷制であったと

いう点で共通点があります。

しかし、「慰安婦」 制度は、主に日本軍が慰安所を設立し、「慰安婦」 を採用したことから、認可され

た売春制度とは異なっていた。

また、日本人の 「慰安婦」 の多くは売春婦の免許を持っていたが、芸者や酌婦は強制的に働かされ

たが、日本の植民地や占領地では 「慰安婦」 にならざるを得なかった。

売春とは何の関係もなく、暴力、欺瞞、人身売買を利用して、日本軍または軍から指示された請負業

者による契約なしに採用されました。

これらの事実は、個人的な証言だけでなく、公式文書を含む膨大な量の歴史的記録に基づく奨学金

によっても証明されています。11

Thirdly, when he explains his own claims, Ramseyer did what a scholar ought not to do, which is to

arbitrarily pick the parts in the materials and historical documents that are convenient for his own

claims and to ignore those that are inconvenient.

With abundant historical resources, scholarship has revealed the two points I raised above, that is,

that (1) licensed prostitution contracts were human trafficking contracts, and (2) while both licensed

prostitution and the Japanese military "comfort women" system were forms of sexual slavery, they

were different in that the Japanese military "comfort women" system was a product of the military.

Because it was difficult to disprove (1) and (2), Ramseyer tried to justify his argument with an

unworthy act of selective scholarship.

第三に、ラムザイヤーは自分の主張を説明するときに、学者がすべきではないことをしました。

それは、自分の主張に便利な資料や歴史的文書の部分を恣意的に選び、不便な部分を無視するこ

とです。

豊富な歴史的資源により、奨学金は私が上記で提起した2つのポイントを明らかにしました。

つまり、(1)認可された売春契約は人身売買契約であり、(2)認可された売春と日本軍の「慰安婦」制

度はどちらも性的奴隷制は、日本軍の 「慰安婦」 制度が軍の産物であるという点で異なっていました。

(1)と(2)を反証することは困難だったので、ラムザイヤーは選択的な学問の価値のない行為で彼の

議論を正当化しようとしました。

1-2. The Purpose of this Article

1-2。この記事の目的

Therefore this article aims to verify the sections in the Ramseyer article that discuss prewar

Japanese licensed prostitutes and brothels by checking the documents and historical records on

which he relies.

I show how Ramseyer builds his argument by deliberately using only those parts of the documents

and historical materials that are convenient for his argument while ignoring those that are

inconvenient -- an improper manipulation as a scholar -- and prove that his article does not meet

academic standards.

Because the licensed prostitute contract in prewar Japan is the starting point for his discussion, it

is meaningful to examine and criticize his view of it in order to show how his article on the problem

of Japanese military "comfort women" falls short.

したがって、この記事は、ラムザイアーの記事の中で、戦前の日本の売春宿と売春宿について論じて

いるセクションを、彼が依存している文書と歴史的記録をチェックすることによって検証することを目的

としています。

ラムザイヤーが、彼の議論に便利な文書と歴史資料の部分だけを意図的に使用し、不便な部分(学

者としての不適切な操作)を無視して、ラムザイヤーがどのように議論を構築するかを示し、彼の記事

が学術に適合しないことを証明します標準。

戦前の日本で認可された売春婦契約が彼の議論の出発点であるため、日本軍の 「慰安婦」 の問題

に関する彼の記事がいかに不十分であるかを示すために、彼の見解を調べて批判することは意味が

あります。

In the next section, I briefly explain findings from previous studies of licensed prostitutes'

contracts in Japan, and use them to examine Ramseyer's argument regarding licensed prostitutes.

次のセクションでは、日本での認可された売春婦の契約に関する以前の研究からの発見を簡単に説

明し、認可された売春婦に関するラムザイヤーの議論を調べるためにそれらを使用します。

2. What are the Licensed Prostitutes’ Contracts?

2.認可された売春婦の契約とは何ですか?

2-1. Human Trafficking

2-1。人身売買

While his revisionist claims about "comfort women" have been discussed in detail by scholars like

Yoshimi Yoshiaki, Ramseyer's claims about contracts for licensed prostitution have received less

scrutiny. Under the licensed prostitution system in modern Japan, women 18 years or older would

apply to the police for a license.

To become a prostitute, both the woman and her parents or guardians needed to sign and seal the

contract.

The actual party to the contract was often the parents or guardians, not the woman herself. The

contract set a term of service (the period of indenture) and she borrowed an advance called

zenshakkin from the owner of the brothel.

The money equivalent for the term zenshakkin had been called minoshiro or minoshirokin meaning "

human collateral" or "ransom money" in premodern Japan, but was subsequently changed to

zenshakkin (advance) in order to hide the fact of human trafficking.12

Women who became licensed prostitutes had virtually no freedom to quit and were forced to sell

sex until they completed their term of service or paid back their advance.13

「慰安婦」 についての彼の修正主義者の主張は吉見義明のような学者によって詳細に議論された

が、認可された売春の契約についてのラムザイヤーの主張はあまり精査されていない。

現代日本の売春免許制度では、18歳以上の女性が警察に免許を申請します。

売春婦になるには、女性とその両親または保護者の両方が契約書に署名して封印する必要があり

ました。

契約の実際の当事者は、多くの場合、女性自身ではなく、両親または保護者でした。契約はサービス

期間(契約期間)を設定し、彼女は兄弟の所有者から前借金と呼ばれる前払い金を借りました。

前借金という言葉に相当するお金は、前近代の日本では 「人の担保」 または 「身代金」 を意味する

身代または身代金と呼ばれていましたが、その後、人身売買の事実を隠すために前借金(アドバンス)

に変更されました。

認可された売春婦になった女性は、事実上、辞める自由がなく、任期を終えるか、前払い金を返済す

るまで、セックスを売ることを余儀なくされた。13

Moreover, prostitutes had to have permission from the police in order to leave the licensed

brothel district (Article Seven, Item Two, Regulations for Licensed Prostitutes, which was rescinded

in 1933).14

Brothel owners would obstruct women from exiting prostitution. When women brought their closing

applications to the police, the police officers would sometimes try to convince them not to quit or

would call the brothel owners.

さらに、売春婦は、認可された売春宿地区を去るために警察から許可を得なければなりませんでした

(1933年に取り消された認可された売春婦のための第7条、第2条、規則)。14

売春宿の所有者は、女性が売春をやめるのを妨げるでしょう。

女性が閉会の申請書を警察に持ち込んだとき、警察官は時々、女性に辞めないように説得しようとし

たり、売春宿の所有者に電話したりしました。

Meanwhile, the owners took, as their own share, all or most of agedaikin (the fee for sexual

services paid by customers).

Therefore, the licensed prostitutes' shares were extremely small and they had to keep repaying

the advances from their small income.

As a result, it was difficult to pay back the advances.

While there were differences in repayment systems in different regions, in Yoshiwara, for instance,

a prostitute's share was 0.5 yen of the 2 yen fee, a quarter of the total.

A certain percentage of that 0.5 yen would go to her monthly payment on the advance, the fukin

(a kind of tax), and other obligations.

The remainder was the allowance that a prostitute used to pay for clothes, make-up, hair styling

and so on.

The money that was left was so little that in many cases the women had to borrow more money,

delaying their repayment and adding to their debts.15

Therefore, many people at that time shared an understanding that the licensed prostitute

contract was de facto human trafficking.

その間、所有者は自分の分として、上げ代金(顧客が支払う性的サービスの料金)のすべてまたはほ

とんどを取りました。

したがって、認可された売春婦の株は非常に小さく、彼らは彼らのわずかな収入から前払い金を返

済し続けなければなりませんでした。

その結果、前払金の返済が困難でした。

地域によって返済制度に違いはあるものの、例えば吉原では売春婦のシェアは2円の手数料の0.5円

で、全体の4分の1でした。

その0.5円の一定の割合は、前払い、風金(一種の税金)、およびその他の義務の彼女の毎月の支

払いに使われます。

残りは、売春婦が衣服、化粧、ヘアスタイリングなどに支払うために使用した手当でした。

残されたお金は非常に少なかったので、多くの場合、女性はより多くのお金を借りなければならず、

返済を遅らせ、借金を増やしました。15

したがって、当時の多くの人々は、認可された売春婦契約は事実上の人身売買であるという理解を

共有していました。

2-2. Why did Human Trafficking Persist?

2-2。人身売買が続いたのはなぜですか?

In principle, many of the contracts in prewar Japan mentioned above were found to be legally

invalid. In 1872, the government issued the "Edict for the Liberation of Geisha and Prostitutes"

(Grand Council Proclamation, No. 295) followed by the Ministry of Justice Law No. 22, which

released geisha and licensed prostitutes from their contracts of indenture and invalidated all

contracts for monetary loans. As a result, only prostitutes of their own "free will" were supposed to

be licensed. And yet, as we have seen, many women who signed these contracts were pressured by

their families and had little idea what they were signing.

原則として、上記の戦前の日本の契約の多くは法的に無効であることが判明した。

1872年、政府は「芸者と売春婦の解放に関する勅令」(大評議会宣言、第295号)を発行し、続いて法

務省法第22号を発行し、芸者と売春婦の契約を解除し、無効にしました。

金銭的貸付のすべての契約。

その結果、彼ら自身の 「自由意志」 の売春婦だけが認可されることになっていた。

それでも、私たちが見てきたように、これらの契約に署名した多くの女性は家族から圧力をかけら

れ、彼らが何に署名しているのかほとんどわかりませんでした。

In addition, in 1896, the Supreme Court issued a ruling invalidating "contracts to work for a set

term" saying they imposed illegal physical restraint. In 1900, the Supreme Court also invalidated

contracts that required prostitutes to work at brothels in order to repay their advances.16

The Regulations on Licensed Prostitutes (shogi torishimari kisoku) established in 1900 stipulated

that licensed prostitutes could exit prostitution at will at any time (free exit or jiyu haigyo).

さらに、1896年、最高裁判所は、違法な身体的拘束を課したとして、「一定期間働く契約」 を無効にす

る判決を下した。

1900年、最高裁判所は、売春宿が売春宿で働いて前払い金を返済することを要求する契約も無効に

しました。16

1900年に制定された売春婦規則(娼妓取締規則)は、売春婦はいつでも自由に売春を辞めることが

できると定めていた(自由出口または自由閉業)。

Despite these rulings and laws, human trafficking persisted because the courts in Japan

differentiated between "contracts for prostitution" and "contracts governing advances",and

regarded only the former as invalid. Since the brothels made women borrow the advances in order

to force them to sell their sex and deprive them of their freedom, a contract that forced a woman

to work in prostitution and one which covered the advance were nothing but a single contract for

human trafficking. Nevertheless the courts saw them as two different contracts.17

And the courts decided that prostitutes must repay the advances even after they quit because

the contract for the advances were valid even if the one for prostitution was not. As a result, it

became almost impossible for licensed prostitutes to quit and the practice of human trafficking

continued.

これらの判決や法律にもかかわらず、日本の裁判所は 「売春契約」 と 「売春契約」 を区別し、前者

のみを無効とみなしたため、人身売買は続いた。売春宿は女性に性別を売って自由を奪うために前払

金を借りさせたので、女性に売春で働くことを強制する契約と前払金をカバーする契約は人身売買の

ための単一の契約に他なりませんでした。

それにもかかわらず、裁判所はそれらを2つの異なる契約と見なしました。17

そして、裁判所は、売春の契約が有効でなかったとしても、売春の契約は有効だったので、売春婦は

辞めた後も前払いを返済しなければならないと決定しました。

その結果、認可された売春婦が辞めることはほとんど不可能になり、人身売買の慣行が続いた。

Kawashima Takeyoshi a prominent scholar of sociology of law in postwar Japan, analyzed

prostitute and geisha contracts and stated "the relationship between geisha and prostitutes who

were owned and their owners was that between humans who were bought and humans who bought

them, in other words, slaves and slave owners",18 and the courts' precedents "ended up giving a

certain legal protection for human trafficking".19

戦後日本における法社会学の著名な学者である川島武義は、売春婦と芸者の契約を分析し、「 芸

者と所有された売春婦とその所有者との関係は、購入された人間と購入された人間との関係であっ

た。奴隷と奴隷所有者 」 18 と裁判所の先例は 「 人身売買に対して一定の法的保護を与えることにな

った 」 19。

2-3. The Violation of International Conventions and Domestic Laws

2-3。国際条約および国内法の違反

In fact, licensed prostitution contracts violated at least the following international laws that

existed before the war: the International Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Women

and Children (1921), the International Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Women of

the Full Age (1933, which Japan did not ratify), and the Slavery Convention (1926, which Japan did

not ratify).

Fuse Tatsuji, a lawyer in prewar Japan, said in 1926 that the custom under Japan’s licensed

prostitution system might have violated at least the following domestic laws: Article 90 of the Civil

Code (Legally binding agreements whose aims were contrary to the public order and morals were

deemed void), Article 628 of the Code (When there is an unavoidable reason, either party can

cancel a contract immediately even if both parties have agreed on a term of employment), and

Article 708 of the Code (The party who loans money for an illegal reason cannot demand

repayment).20

実際、認可された売春契約は、少なくとも戦前に存在していた次の国際法に違反していました。

女性と子どもの交通の抑制に関する国際条約(1921)、完全な女性の交通の抑制に関する国際条約

年齢(1933年、日本は批准しなかった)、および奴隷条約(1926年、日本は批准しなかった)。

戦前日本の弁護士である布施辰二氏は、1926年に日本の認可売春制度の下での慣習は少なくとも

以下の国内法に違反した可能性があると述べた。無効とみなされた)、法第628条(やむを得ない理由

がある場合は、両当事者が雇用期間について合意した場合でも、いずれの当事者も直ちに契約を解

除することができる)、法第708条(金銭を貸与する者)違法な理由で返済を要求することはできませ

ん)20

Even mainstream politicians, major newspapers, and the general public shared abolitionists' views

that the licensed prostitute contract was human trafficking and the licensed prostitution system

was slavery.21

The League of Nations' Commission of Enquiry into Traffic in Women and Children in the East who

visited Japan in 1931 also criticized Japan's licensed prostitution system.22

In fact, in the mid-1930s the Home Ministry's Police Affairs Bureau itself equated the licensed

prostitution system to slavery and considered its abolition.23

While revisionists typically offer the argument that the prostitution contract was legal and

acceptable at the time, and contemporary scholars are applying anachronistic moral standards to

the past, it is quite clear that the licensed prostitution contract was considered both morally and

legally dubious at the time, both inside and outside of Japan.

主流の政治家、主要な新聞、そして一般大衆でさえ、認可された売春契約は人身売買であり、認可さ

れた売春システムは奴隷制であるという奴隷制度廃止論者の見解を共有した。

国際連盟の1931年に日本を訪れた東部の女性と子どもの交通に関する調査委員会も、日本の認可

された売春制度を批判した22。

実際、1930年代半ばには、内務省の警察局自体が認可された売春制度と同一視した。

奴隷制になり、その廃止を検討した。23

修正主義者は通常、売春契約は当時は合法で容認できるものであり、現代の学者は時代錯誤的な

道徳基準を過去に適用しているという主張をしますが、認可された売春契約が当時道徳的にも法的に

も疑わしいと見なされていたことは明らかです。 日本の内外の両方。

3. Fact-Checking the Ramseyer Article

3.ファクトチェック-ラムザイヤーの記事を確認する

Let us move to fact check Ramseyer's article, "Contracting for Sex in the Pacific War".

In the section on licensed prostitutes, Ramseyer first describes the main points of the contract

and then uses data to discuss the age of the prostitutes, the numbers of years of continuous work,

their incomes, and the details of repayment on their advances.

ラムザイヤーの記事 「太平洋戦争におけるセックスの契約」 のファクトチェックに移りましょう。

認可された売春婦に関するセクションでは、ラムザイヤーは最初に契約の要点を説明し、次にデータ

を使用して売春婦の年齢、継続労働の年数、収入、および前払金の返済の詳細について話し合いま

す。

3-1. Licensed Prostitutes' Contracts

3-1。認可された売春婦の契約

While he shows no actual contract in his article, Ramseyer explains the terms of the licensed

prostitute's contract as follows on page 2 of his article:

彼は彼の記事に実際の契約を示していませんが、ラムザイヤーは彼の記事の2ページで次のように

認可された売春婦の契約の条件を説明しています。

a.The brothel paid the woman (or her parents) a given amount upfront, and in exchange she

agreed to work for the shorter of (i) the time it took her to pay off the loan or (ii) the stated

contractual term

売春宿は女性(または彼女の両親)に前払いで一定の金額を支払い、その代わりに彼女は(i)ロ

ーンの返済にかかった時間または(ii)定められた契約期間のいずれか短い方で働くことに同意しまし

た

b.The mean upfront amount in the mid-1920s ranged from about 1000 to 1200 yen.

The brothel did not charge interest.

1920年代半ばの平均前払い額は約1000円から1200円の範囲でした。

売春宿は利息を請求しませんでした。

c.The most common (70-80 percent of the contracts) term was six years.

最も一般的な(契約の70-80パーセント)期間は6年でした。

d.Under the typical contract, the brothel took the first 2/3 to 3/4 of the revenue a prostitute

generated.

It applied 60 percent of the remainder toward the loan repayment, and let the prostitute keep the

rest.

典型的な契約では、売春宿は売春婦が生み出した収入の最初の2/3から3/4を取りました。

残りの60%をローン返済に充て、残りは売春婦に預けました。

Ramseyer's claims about the contract are based on the following works as cited in his footnote 2

on page 2:

Fukumi Takao's Teito ni okeru baiin no kenky?,24 Kusama Yasoo's Jokyu to baishofu,25 Okubo

Hasetsu's Kagai fuzoku shi,26 Ito Hidekichi's Kotoka no kanojo no seikatsu,27 and Gei shogi shakufu

shokaigyo ni kansuru chosa.28

Let us look at the contents of the contracts published in these works.

契約に関するラムザイヤーの主張は、2ページの脚注2に引用されている

次の著作に基づいています。

副見喬の帝都におけるばいんの研究、24

草間彌生の承久の乱とばいしょふ、25

大久保はせつにかがい風俗史、26

伊藤秀吉のこうとかのかの情操の内容28

これらの作品で公開された契約。

Jokyu to baishofu introduces three licensed prostitution contracts signed in 1911, 1914, and 1923.

The contracts included in the book are the ones in 1914 and 1923 and are the same as those in

the survey by Chuo shokugyo shokai jimukyoku (The Central Office of Employment) since Kusama,

the author of the book, also conducted the survey. Both Kotoka no kanojo no seikatsu and Kagai

fuzoku shi have a contract.

First, let us look at the 1924 contract included in Joyku to baishofu29 as well as Geishogi shakufu

shokaigyo ni kansuru chosa.

The underlines are mine.

ばいしょうふの状況は、1911年、1914年、1923年に署名された3つの売春契約を紹介します。

本書に含まれる契約は、1914年と1923年のものであり、本の著者である草間も調査を行ったため、

中王食行書会事務局(中央雇用局)による調査と同じである。

コトカの彼女生活と加害風俗史の両方が契約を結んでいます。

まず、上級とばいしょうふ 29 と 芸娼妓者くふ紹介業に関する調査に含まれる1924年の契約を見て

みましょう。 下線は私のものです。

The contract

その契約

I hereby enter into the following contract for engaging in the work of prostitution at your

establishment.

私はここにあなたの施設で売春の仕事に従事するために以下の契約を結びます。

Article 1: I will stay at your establishment and engage in prostitution under your direction and

supervision for a period of six years beginning on the date of registration in the licensed prostitute

directory.

第1条:私はあなたの施設に滞在し、あなたの指示と監督の下で、認可された売春婦登録への登録

日から6年間、売春を行います。

Article 2: I borrowed 2,400 yen from you.

第2条:あなたから2,400円借りました。

Article 3: The cash advance mentioned in the previous article must be returned using the income I

earn from the prostitute business.

第3条:前の記事で述べた借金は、私が売春婦の事業から得た収入を使って返還されなければなり

ません。

(Provisions) The fee per night is two yen.

1.2 yen shall be your income and the remaining 0.8 yen is mine. 0.5 yen of this 0.8 yen will go to

the repayment of my loan and 0.3 yen shall be my allowance.

(引当金)1泊2円です。

収入は1.2円、残りの0.8円は私の収入です。この0.8円のうち0.5円が私のローンの返済に使われ、0.3

円が私の手当になります。

Article 4: If I temporarily borrow money beyond the advance mentioned in Article 2,or you pay for

my expenses, I must pay back the money I owe you following the previous article’s provisions.

第4条:第2条に記載された前払金を超えて一時的に借金をした場合、またはあなたが私の費用を支

払った場合、前の条の規定に従ってあなたに借りているお金を返済しなければなりません。

Article 5: You will pay for all expenses such as daily meals and necessary items for the room

rented for my work, and I will pay for kimono for each of the four seasons and other necessary

items for myself.

第5条:私の仕事のために借りた部屋の日食や必要なものなどのすべての費用はあなたが負担し、

四季ごとの着物やその他の必要なものは自分で支払います。

Article 6: I will pay for my own medical expenses if I receive treatment at any hospital other than

Yoshiwara Hospital.

第6条:吉原病院以外の病院で治療を受けた場合は、自己負担となります。

Article 7: I will provide all of my possessions as collateral for my advance and will not have control

over them.

第7条:私はすべての所有物を私の前進の担保として提供し、それらを管理することはできません。

Article 8: If you sell your brothel to someone else or need to transfer me to another, I will follow

your direction without objection from myself or my joint guarantors.

第8条:売春宿を他の人に売ったり、私を別の人に譲渡したりする必要がある場合、私は私自身また

は私の共同保証人からの異議なしにあなたの指示に従います。

Article 9: If I escape, my joint guarantors will immediately search for me and make me go back to

work, and I accept that my term of service will be extended for the number of days that I was gone.

第9条:私が逃げた場合、私の共同保証人はすぐに私を探して仕事に戻らせ、私の任期は私が去っ

た日数だけ延長されることを受け入れます。

Article 10: If I die, my joint guarantors will take my body and proceed to prepare for a funeral.

第10条:私が死んだ場合、私の共同保証人は私の体を取り、葬式の準備に進みます。

(Provisions) If the duties mentioned in the previous articles are not completed, you will take

appropriate measures and my joint guarantors will pay the cost.

(規定)前条の義務が果たされない場合は、適切な措置を講じ、共同保証人が費用を負担します。

Article 11: If I violate this contract, I will be responsible for reimbursing you for any damage I cause.

第11条:私がこの契約に違反した場合、私は私が引き起こしたいかなる損害についてもあなたに払

い戻す責任があります。

Article 12: I agree that the Tokyo district court has jurisdiction over any lawsuits concerning this

contract.

第12条:東京地方裁判所が本契約に関する訴訟を管轄することに同意します。

July 20, 1923

1923年7月20日

Father: Kuroda Hachibei

父:黒田八兵衛

Mother: Kuroda Saki

母:黒田咲

Prostitute: Kuroda Take

売春婦:黒田テイク

Brothel: Ando Kinjiro

売春宿:安藤金次郎

(all are pseudonyms)

(すべて仮名です)

We can see that there are many other agreed items besides the term of indenture, the amount of

the advance, the distribution of income and the method of repayment that Ramseyer points out. All

of them, where I have underlined above, deprive the licensed prostitute of her freedom. For

example, (1) the licensed prostitute does not own most of her possessions since they are collateral

for her advance (Article 7); (2) neither the prostitute nor her parents can oppose the owner's will

when someone else purchases the brothel she works at or if she moves to another brothel (Article

8). In addition, it is clear that the joint-guarantors were responsible if the prostitute escaped or did

not fulfill her duties. (3)

Her parents who are joint guarantors are bound to bring her back if she escapes, and the period

of her flight will be added onto her term (Article 9).

ラムザイヤーが指摘しているように、契約期間、前払金の額、所得の分配、返済方法以外にも、合意

された項目がたくさんあることがわかります。

私が上で強調したそれらのすべては、認可された売春婦から彼女の自由を奪います。

たとえば、(1)認可された売春婦は、彼女の前進の担保であるため、彼女の所有物のほとんどを所

有していません(第7条)。

(2)売春宿もその両親も、他の誰かが彼女が働いている売春宿を購入したとき、または彼女が別の

売春宿に引っ越した場合、所有者の意志に反対することはできません(第8条)。

さらに、売春婦が逃亡した場合、または彼女の義務を果たさなかった場合、共同保証人が責任を負

っていたことは明らかです。 (3)

共同保証人である彼女の両親は、彼女が逃げた場合、彼女を連れ戻す義務があり、彼女の飛行期

間は彼女の任期に追加されます(第9条)。

The licensed prostitutes' contracts included in the books that Ramseyer refers to in his article,

such as Kotoka no kanojo no seikatsu and Kagai fuzoku shi, include similar articles to the one shown

above.

Moreover, in the former, there are contracts which include articles like "the term of service will be

extended when the prostitute fails to pay back her advance by the end of the term"; "The

prostitute pays the entertainment tax if her customer does not"; "Her joint guarantors pay for the

rest of her unpaid advance when the prostitute dies"; "Her joint guarantors repay the advance

when the prostitute escapes. 30

The contract included in Kagai fuzoku shi has an article that says "the owner of the brothel will

confiscate all of her possessions if the prostitute is not able to repay the advance by the end of the

term". 31

ラムザイヤーが彼の記事で言及している本に含まれている認可された売春婦の契約には、上記と同

様の記事が含まれています。さらに、

前者には、「 売春婦が期間の終わりまでに前払い金を返済しなかった場合、サービス期間が延長さ

れる 」 などの条項を含む契約があります。

「 売春婦は、顧客が支払わない場合、娯楽税を支払います 」;

「 彼女の共同保証人は、売春婦が亡くなったときに彼女の未払いの前払い金の残りを支払います 」;

「 彼女の共同保証人は、売春婦が逃げたときに前払い金を返済します。 30

売春宿風俗市に含まれる契約には、「 売春宿の所有者は、売春婦が最後まで前払い金を返済でき

ない場合、すべての所有物を没収します。 用語の。31

Nevertheless, Ramseyer completely ignores these articles that deprive licensed prostitutes of

their freedom. He does not mention them at all in his article. Isn't this because they are

inconvenient for his argument that women made contracts with their owners on an equal footing

and they can feel free to quit their jobs?

Ramseyer writes that the licensed prostitutes "understood too that they could shirk or disappear

" and "In cities like Tokyo, they could easily leave their brothels". 32

The contracts provide no evidence of this; in fact, these terms omitted in Ramseyer's analysis

strongly suggest the opposite. It shows that it was hard for licensed prostitutes to exit the brothels.

それにもかかわらず、ラムザイヤーは、認可された売春婦の自由を奪うこれらの記事を完全に無視

しています。彼は彼の記事でそれらについて全く言及していません。

これは、女性がオーナーと対等な立場で契約を結び、気軽に仕事を辞めることができるという彼の主

張に不便だからではないでしょうか。

ラムザイヤーは、認可された売春婦は 「 彼らが身をかがめたり消えたりする可能性があることも理

解していた 」 と 「 東京のような都市では売春宿を簡単に離れることができる 」 と書いている。 32

契約はこれの証拠を提供しません。

実際、ラムザイヤーの分析で省略されたこれらの用語は、反対のことを強く示唆しています。

それは、認可された売春婦が売春宿を出るのが難しかったことを示しています。

Indeed, there must have been a wide range of contracts and the conditions for the licensed

prostitutes might have improved in subsequent years, perhaps influenced by the movement for the

abolition of licensed prostitution or by strikes conducted by the prostitutes themselves.

Yet Ramseyer relies on the materials mentioned above. If the purpose of his article is to discuss

the terms specified in the contracts, it is inconceivable that he would ignore parts of them just

because they are inconvenient.

確かに、さまざまな契約があったに違いなく、認可された売春婦の条件は、おそらく認可された売春

の廃止運動または売春婦自身によるストライキの影響を受けて、その後数年で改善された可能性があ

ります。

しかし、ラムザイヤーは上記の資料に依存しています。

彼の記事の目的が契約で指定された条件を議論することである場合、それらが不便であるという理

由だけで彼がそれらの一部を無視することは考えられません。

Meanwhile, Ramseyer writes that if women shirked or escaped, "the brothel would then sue their

parents to recover the cash advance (a prostitute's father typically signed the contract as

guarantor). That this only happened occasionally suggests (obviously does not prove) that most

prostitutes probably chose the job themselves". 33

What is Ramseyer suggesting here, and does it accord with what we know about this contracts

and their context?

Ramseyer seems to be implying that the fact that women infrequently escaped ? even though the

burden would fall on their parents, rather than on them as individuals, if they did ? means that

women were content to labor in brothels. But how do we know this?

Ramseyer frequently cites Teito ni okeru baiin no kenky?, which proposes the opposite argument:

“Her parents or her closest relatives become her guarantors and, if the prostitute fails to pay back

exactly the amount of the contract, they are collectively responsible and the collection of the debt

is immediately legally enforceable.

Therefore even if a licensed prostitute wanted to quit, it is difficult for her to do so unless she

finished paying back her advance if she does not want to cause trouble for others". 34

In a later section, it continues, "Most licensed prostitutes try to pay what their parents ask no

matter what pain they have to go through or embarrassment they have to endure. Every brothel

owner unanimously praises these women saying "No one must be more thoughtful of her parents

than licensed prostitutes". 35

Anyone who studies modern Japanese history knows that family morality was imprinted onto the

daughters.

Because the contracts took advantage of this, the licensed prostitutes thought they could not

distress their parents, who were their joint guarantors, and this emotional bond meant that they

were not able to escape.

Ramseyer entirely disregards this explanation, which is proposed in the very sources he cites.

一方、ラムザイヤーは、女性が身をかがめたり逃げたりした場合、「 売春宿は両親に現金前貸しを

取り戻すように訴えるだろう (売春婦の父親は通常保証人として契約に署名した)」 と書いている。

「 売春宿はおそらく自分たちで仕事を選んだのだろう 」 と語った。 33

ラムザイヤーはここで何を示唆していますか、そしてそれはこの契約とその文脈について私たちが知

っていることと一致していますか?

ラムザイヤーは、女性が逃げることがめったにないという事実は、たとえ個人としてではなく両親に負

担がかかるとしても、女性が売春宿で働くことに満足していることを意味しているようです。

しかし、どうやってこれを知るのでしょうか?

ラムザイヤーは、反対の主張を提案する 「 帝都に於ける売淫の研究 」 を頻繁に引用している。

債務は直ちに法的強制力があります。

したがって、「 認可された売春婦が辞めたいと思ったとしても、他人に迷惑をかけたくないのであれ

ば、前払い金の返済を終えない限り、辞めることは難しい 」 と述べた。

後のセクションでは、「 ほとんどの認可された売春婦は、どんな苦痛や恥ずかしさに耐えなければな

らないかに関わらず、両親が求めるものを支払おうとします。 すべての売春宿の所有者は、満場一

致でこれらの女性を称賛します。 認可された売春婦よりも彼女の両親の 」 35

現代日本の歴史を研究する人なら誰でも、家族の道徳が娘たちに刻印されていることを知っていま

す。

契約がこれを利用したので、認可された売春婦は彼らが彼らの共同保証人である彼らの両親を苦し

めることができないと思いました、そしてこの感情的な絆は彼らが逃げることができなかったことを意味

しました。

ラムザイヤーは、彼が引用しているまさにその情報源で提案されているこの説明を完全に無視してい

ます。

In addition, Jokyu to baishofu and Kagai fuzokushi, both sources on which Ramseyer relies heavily,

say that complex circumstances went into making contracts so as to hide the reality of the licensed

prostitute contract.

This was because, as mentioned above, a contract forcing a licensed prostitute to work

involuntarily was invalidated by the courts.

As a result, an increasing number of brothel owners did not stipulate in official contracts (kosei

shosho) that they were making women engage in prostitution but instead privately made a licensed

prostitution contract.

また、ラムザイヤーが大きく依存しているばいしょうふの状況と加害風俗師は、免許を持った売春婦

契約の現実を隠すために、複雑な事情で契約を結んだと述べている。

これは、前述のように、免許を持った売春婦に無意識に働くことを強制する契約が裁判所によって無

効にされたためです。

その結果、売春宿の所有者の多くは、女性を売春に従事させることを公式の契約(公正証書)で規定

せず、代わりに私的に認可された売春契約を結んだ。

As Jokyu to baishofu explains, because a notarized contract could be legally enforced, it could

come into play in a conflict between the prostitute or her parents and the owner.

If a dispute arose over repayment of an advance, a court would likely rule a contract invalid if the

owner provided a notarized contract that mentioned the woman was made to be a prostitute

involuntarily since, as explained above, any contract forcing a woman into prostitution against her

will was invalid.

Because of this, brothel owners became more artful. Even when they used a notarized contract,

the book says, they would take care to mention nothing about licensed prostitution, but rather made

it merely a financial contract, consigning all wording related to a woman's role and work conditions

as a prostitute to a private contract.36

The licensed prostitution contract of 1923 shown above was in fact a private contract. Separate

from this contract, Kusama says that the parties also signed a notarized contract, shown below.37

売娼婦の状況が説明するように、公証された契約は法的に執行される可能性があるため、売春婦ま

たはその両親と所有者との間の紛争に巻き込まれる可能性があります。

前払金の返済をめぐって紛争が発生した場合、上で説明したように、女性を売春に追いやる契約が

あるため、所有者が女性を強制的に売春婦にしたことを示す公証契約を提出した場合、裁判所は契

約を無効と判断する可能性があります。 彼女の意志は無効でした。

このため、売春宿の所有者はより巧妙になりました。彼らが公証された契約を使用した場合でも、彼

らは認可された売春については何も言及しないように注意し、むしろそれを単なる金融契約にし、売春

婦としての女性の役割と労働条件に関連するすべての文言を私的契約に委託したと本は述べていま

す.36

上に示した1923年の認可された売春契約は、実際には私的な契約でした。この契約とは別に、草間

は、当事者が以下に示す公証契約にも署名したと述べています37。

The financing contract (original)

融資契約(原本)

I describe the contents of statements from each party as follows.

各当事者の発言内容は以下のとおりです。

Article 1: On July 20, 1923, And? Kinjir? lent 2,400 yen to Kuroda Hachibei and Kuroda Saki, and

the latter parties jointly borrowed the money based on this contract (the names are pseudonyms).

第1条:1923年7月20日、安藤金次郎は黒田八兵衛と黒田咲に2,400円を貸与し、後者はこの契約に

基づいて共同で資金を借り入れた(名前は仮名)。

One: The principal must be returned by August 20, 1923.

1つ:元本は1923年8月20日までに返還されなければなりません。

Two: Interest is 10% per year and Kuroda must pay this on top of the principal.38

2:利息は年間10%であり、黒田は元本に加えてこれを支払う必要があります。38

Three: Even after the end of the term, Kuroda must compensate for any damage until the

repayment is complete, following the interest rate agreed in the contract.

3:期間終了後も、黒田は契約で合意された金利に従い、返済が完了するまで損害を補償しなければ

なりません。

Article 2: Debtors agreed that this contract can be legally enforced immediately upon failure to

repay the advance in the contract.

第2条:債務者は、契約の前払い金の返済に失敗した場合、直ちにこの契約を法的に執行できること

に同意しました。

This contract entered into at the government office on July 20, 1923.

I read it aloud to each party and they all agreed.

Therefore with me they signed and sealed here as follows.

この契約は1923年7月20日に官庁で締結されました。

私はそれを各当事者に声を出して読み、全員が同意しました。

したがって、私と一緒に、彼らはここで次のように署名して封印しました。

This notarized contract mentions only the repayment date, the rate of interest, and the legal

enforceability in case of failure to pay.

It does not say anything about making the woman serve as a prostitute against her will. It works

for the brothel owner since there is no worry that a court could rule the contract invalid if

something happens.

Also, because it is notarized, it can be enforced without a court's intervention. Yet, Kusama writes,

"a question comes to my mind when I look at this notarized contract very carefully. It is the date of

payment in item one of Article 1. The loan of 2400 yen to Kuroda was dated July 20, 1923; the

repayment date was the following month, on August 20. They were given only 30 days. How could

they repay a debt of 2,400 yen in one month, a sum they borrowed by selling their daughter

because they were so poor? Needless to say, that's impossible".

If this was the case, why did the contract provide such a short term for repayment?

Kusama argues that brothel owners set a short term for repayment because prostitutes were

legally entitled to quit their jobs at any time.

"If [the date of payment] is set for a short term, say one month after signing the contract,

brothel owners can legally seize the parents' property immediately upon a prostitute's quitting. They

then postpone collecting the loan if the prostitute continues to work. The sharp sword of this

obligation, and its potential execution as soon as a month after starting work, is always dangling over

her head".

At the same time, as we saw previously, the women were forced to explicitly promise to carry out

the duties of being a prostitute by signing a private contract. These were clever methods that

brothel owners created as prewar courts regarded the prostitute contract as separate from the

contract for the advance, and saw the latter as valid. In order to discuss the licensed prostitute

contract, we have to consider not only the contract itself but also these circumstances.39

この公証された契約には、返済日、利率、および支払いを怠った場合の法的強制力のみが記載され

ています。

それは、女性を彼女の意志に反して売春婦として仕えることについては何も述べていません。

何かが起こった場合に裁判所が契約を無効と判断する心配がないので、売春宿の所有者のために

機能します。

また、公証されているため、裁判所の介入なしに執行することができます。

しかし、草間氏は、「 この公証契約をよく見ると、疑問が浮かぶ。 第1条第1項の支払日である。

黒田への2400円の貸付は、1923年7月20日である。 返済日は翌月の8月20日で、30日しか与えられ

なかったのですが、貧しかったので娘を売って借りた1ヶ月で2,400円の借金をどうやって返済できるの

でしょうか。 不可能。」

もしそうなら、なぜ契約はそのような短期間の返済を提供したのでしょうか?

草間は、売春宿はいつでも法的に仕事を辞める権利があるので、売春宿の所有者は返済のための

短期を設定したと主張している。

「 [支払い日] が短期、たとえば契約締結後1か月に設定されている場合、売春宿の所有者は、売春

婦が辞めた直後に親の財産を合法的に差し押さえることができます。

その後、売春婦が働き続ける場合は、ローンの回収を延期します。

この義務の鋭い剣と、仕事を始めてから1か月後すぐに実行される可能性のあるものは、常に彼女

の頭上にぶら下がっています。

同時に、私たちが以前に見たように、女性は私的な契約に署名することによって売春婦であるという

義務を遂行することを明示的に約束することを余儀なくされました。

これらは、売春宿の所有者が戦前の裁判所として作成した巧妙な方法であり、売春婦の契約は前払

いの契約とは別のものであり、後者は有効であると見なされていました。

認可された売春婦契約について議論するためには、契約自体だけでなく、これらの状況も考慮する

必要があります39。

I also have to comment on Ramseyer's descriptions of the amount of the advance, the term of

service, and the interest.

It seems that he described the average amount of the advances as between 1,000 and 1,200 yen

in the mid-1920s40 because the most common amount was between 1,000 and 1,200 yen in Teito ni

okeru baiin no kenky?.41 However, that data is for licensed prostitutes in Tokyo and we should

remember that the advances varied in different areas.

The length of the term of service also depended on the area they worked.42

また、ラムザイヤーの前払額、サービス期間、および利息の説明についてもコメントする必要があり

ます。

1920年代半ばの平均前払額は1,000円から1200円だったとのことであるが 40、そのデータは売春婦

の免許を持った売春婦のデータである。

東京では、進歩は地域によって異なることを覚えておく必要があります。

勤続期間の長さも彼らが働いた地域に依存した 42。

At the same time, Ramseyer's claim that "brothels did not charge interest" 43 is false, even in

Tokyo.

In Teito ni okeru baiin no kenky?, upon which he relies heavily, author Fukumi writes "Although as a

general rule brothels do not require interest be paid on the advance, there are places requiring 7.2%

per year or 6% per year depending on the designated zone. Even in zones where no interest was

charged, when a prostitute quits or changes owner, there are cases where they are charged 10% or

12 % per year". 44

同時に、「 売春宿は利息を請求しなかった 」 というラムザイヤーの主張 43 は、東京でも誤りであ

る。

執筆者の福見氏は、頼りになる 「帝都におけるばいんの研究」 の中で、「 売春宿は原則として前払

いで利息を払う必要はないが、年に7.2%、年に6%かかるところもある。 指定ゾーン。 利息が請求さ

れていないゾーンでも、売春宿が辞めたり、所有者を変更したりすると、年間10%または12%が請求さ

れる場合があります。」 44

3-2. On the Age of Licensed Prostitutes

3-2。認可された売春婦の時代について

Next, Ramseyer writes "If brothels manipulated charges or otherwise cheated on their term to

keep prostitutes locked in debt, the number of licensed prostitutes would have stayed reasonably

constant at least up to age 30. 45

次に、ラムザイヤーは次のように書いています。 「 売春宿が売春宿を借金に閉じ込めておくために

容疑を操作したり、他の方法で騙されたりした場合、認可された売春婦の数は少なくとも30歳まではか

なり一定に保たれたでしょう。」 45

To be clear, even if the brothel kept the term of service agreed to under the contract, making

women work as prostitutes repay the debt itself was legally invalid.46

明確にするために、売春宿が契約の下で合意された勤続期間を維持したとしても、売春婦として女性

を働かせることは、借金自体を返済すること自体が法的に無効でした。

Citing Teito ni okeru baiin no kenkyu,47 Ramseyer writes:

統計に於ける売淫の研究を引用して47、ラムザイヤーは次のように書いています。

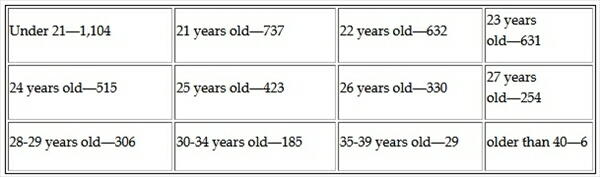

"In 1925, there were 737 licensed Tokyo prostitutes aged 21, and 632 aged 22. There were only

515 aged 24, however, 423 age 25, and 254 age 27." 48

「 1925年には、21歳の東京の売春婦は737人、22歳の売春婦は632人でした。 24歳の売春婦は515

人でしたが、25歳の423人、27歳の254人でした。」 48

But the actual numbers cited in the book is the following:

しかし、本で引用されている実際の数は次のとおりです。

In other words, Teito ni okeru baiin no kenkyu that Ramseyer refers to shows the numbers of

licensed prostitutes who were not only older than 28 years old but also older than 40.

The census found 526 licensed prostitutes who were older than 28, accounting for more than 10

percent of the total.

But for readers of Ramseyer's article it reads as if there were no licensed prostitutes older than

28. Meanwhile, Fukumi, the author of the book and an inspector in the Tokyo Metropolitan Police

Department, wrote: "We have to recognize that those licensed prostitutes who were older than 30

years old numbered 220, which is significant when compared with the total of 5,152. We can imagine

that numerous painful facts must exist behind these numbers." 49

Ramseyer ignored these inconvenient facts?the numbers of licensed prostitutes recorded in the

material on which he himself relies?to justify his argument that women were not restrained by the

brothels for a long time.

つまり、ラムザイヤーが言及している 「帝都に於ける売淫の研究」 は、28歳以上40歳以上の売春婦

の数を示している。

国勢調査では、28歳以上の認可された売春婦が526人見つかり、全体の10パーセント以上を占めて

います。

しかし、ラムザイヤーの記事の読者にとっては、28歳以上の売春婦がいないかのように読めます。

一方、本の著者で警視庁の検査官である福見は、次のように書いています。 「 30歳以上の220とい

う数字は、合計5,152と比較すると重要です。 これらの数字の背後には、多くの痛ましい事実が存在し

ているに違いないと想像できます。」 49

ラムザイヤーは、女性が売春宿に長い間拘束されていなかったという彼の主張を正当化するため

に、これらの不便な事実(彼自身が依拠する資料に記録された認可された売春婦の数)を無視しまし

た。

Another important point as far as numbers of licensed prostitutes is that there were 1,104

licensed prostitutes who were under 21 years old; it is clear that this age group was larger than any

other.

But Ramseyer omits this number.

The Japanese licensed prostitution system allowed minors as young as 18 to become prostitutes,

which means that their parents were de facto the contracting parties.

The fact that a large number of licensed prostitutes were under 21 years old is indeed

inconvenient for his view that the women negotiated and signed their contracts as their own agents.

認可された売春婦の数に関するもう一つの重要な点は、21歳未満の認可された売春婦が1,104人い

たことです。この年齢層が他のどの年齢層よりも大きかったことは明らかです。

しかし、ラムザイヤーはこの番号を省略しています。

日本の認可された売春制度は、18歳の未成年者が売春婦になることを許可しました。

これは、彼らの両親が事実上契約当事者であったことを意味します。

認可された売春婦の多くが21歳未満であったという事実は、女性が彼ら自身の代理人として彼らの

契約を交渉し、署名したという彼の見解にとって確かに不便です。

3-3. Prostitutes’ Years of Service

3-3。売春婦の勤続年数

Moreover, Ramseyer states: "if brothels were keeping prostitutes locked in debt slavery, the

number of years in the industry should have stayed constant beyond six. Yet of 42,400 licensed

prostitutes surveyed, 38 percent were in their second or third year, 25 percent were in their fourth

or fifth, and only 7 percent were in their sixth or seventh". 50

In other words, he insists that licensed prostitutes must have been able to quit after a short

period of work.

さらに、ラムザイヤーは次のように述べています。

「 売春宿が売春婦を借金奴隷制に閉じ込めていたとしたら、業界の年数は6年を超えて一定に保た

れるはずでした。彼らの4番目か5番目に、そして7パーセントだけが彼らの6番目か7番目にありまし

た 」 50

言い換えれば、彼は、免許を持った売春婦は、短期間の仕事の後に辞めることができたに違いない

と主張している。

But Ramseyer disregards an important description in the material he relies on.

His citations include Ito Hidekichi's Kotoka no kanojo no seikatsu and Kusama Yasoo's Jokyu to

baishofu.

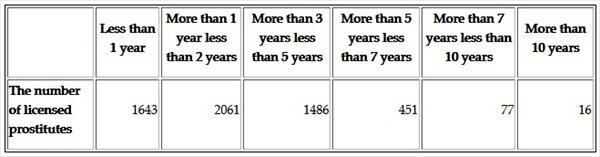

The latter reports the number of years of service for licensed prostitutes in Tokyo based on with

a survey by the Tokyo Metropolitan Police as of the end of December in 1927.51

しかし、ラムザイヤーは、彼が依存している資料の重要な説明を無視しています。

彼の引用には、伊藤秀吉のコトカの彼女の生活、草間靖の売娼婦の状況があります。

後者は、1927年12月末現在の警視庁の調査に基づいて、東京で認可された売春婦の勤続年数を報

告している。51

Survey by Tokyo Metropolitan Police as of December 31, 1927

1927年12月31日現在の警視庁による調査

* Provided that these are years worked at the current brothel.

* これらが現在の売春宿で働いていた年であるという条件で。

The number of years of service for licensed prostitutes in Tokyo as of December 31, 1927,from a

survey by the Tokyo Metropolitan Police, as published in Kusama Yasoo Jokyu to baishofu, 281.

1927年12月31日現在の東京での認可された売春婦の勤続年数。

警視庁の調査による、草間靖の売娼婦の状況、281に掲載されています。

Indeed, the number of licensed prostitutes who worked fewer than five years is large.

Yet, what is important is the proviso which says "these are years worked at the current brothel".

Ramseyer does not mention this note at all in his article. In other words, in Joky? to baishofu,

Kusama explains that these numbers do not reflect how many years the licensed prostitutes worked

in total, but rather how many they worked at their current brothel.

The data does not count years of service at any different brothel the women were subsequently

relocated (sold) to. So while the chart shows that a majority worked fewer than two years at their

current brothel, it is likely, given what we know about working conditions, that they were then

transferred (sold) to another where they continued to work. In light of this, the chart tells us little

about how easy it was for licensed prostitutes to quit.

確かに、5年未満働いた認可された売春婦の数は多いです。

しかし、重要なのは 「これらは現在の売春宿で働いた年数です」 という但し書きです。

ラムザイヤーは、彼の記事でこのメモについてまったく言及していません。

言い換えれば、上級から売諸婦では、草間は、これらの数字は、認可された売春婦が合計で何年働

いたかではなく、現在の売春宿で何年働いたかを反映していると説明しています。

このデータは、女性がその後転居(売却)された別の兄弟での勤続年数をカウントしていません。

したがって、チャートは大多数が現在の売春宿で2年未満しか働いていないことを示していますが、労

働条件について私たちが知っていることを考えると、彼らはその後別の売春宿に移され(売られ)、そこ

で働き続けた可能性があります。

これに照らして、チャートは、認可された売春婦が辞めることがどれほど簡単であったかについて私

たちにほとんど教えてくれません。

3-4. Details of Exiting Prostitution

3-4。 売春の終了の詳細

As noted above, Ramseyer says that licensed prostitutes were able to exit prostitution easily, but

says nothing about the details of how women left.

Teito ni okeru baiin no kenky?, another source that he relies heavily on, describes in its section on

indenture:

上記のように、ラムザイヤーは、認可された売春婦は売春を簡単に抜け出すことができたと言います

が、女性がどのように去ったかについての詳細については何も述べていません。

彼が大きく依存しているもう1つの情報源である 「帝都に於ける売淫の研究」は、捺印した契約書の

段落で次のように説明しています。

"Opportunities for leaving prostitution receded because around the time their indenture was to

end some prostitutes would be switched to a new brothel and become subject to a new contract".

52

「 売春を辞める機会は、彼らの売春宿が終わろうとしていた頃に、一部の売春宿が新しい売春宿に

切り替えられ、新しい契約の対象となるために後退した 」 52

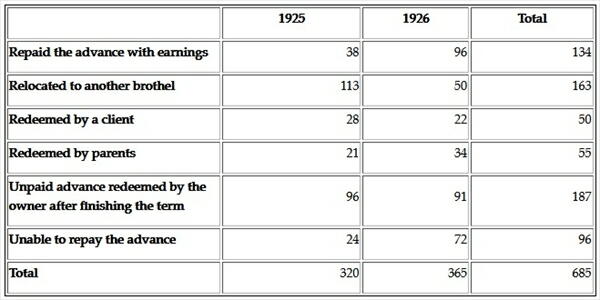

Kusama's Jokyu to baishofu, which Ramseyer relies on as seen above, includes a survey on the

circumstances of prostitutes in one of Tokyo's licensed quarters who exited the brothel. 53

Below is a chart showing the research on the reasons for discontinuing service in Tokyo's Suzaki

Licensed Quarters in 1925 and 1926 ("Geish?gi shakufu shokaigyo ni kansuru chosa" also includes

the 1925 survey).

上記のようにラムザイヤーが頼りにしている草間彌生の売娼婦の状況には、東京の認可された地区

の1つで売春宿を出た売春婦の状況に関する調査が含まれています。 53

以下は、1925年と1926年に東京の須崎認可地区でサービスを停止した理由に関する調査を示した

グラフです ( 「芸者の酌婦業に関する長さ」 には1925年の調査も含まれています)。

While there was some variation by year, those who "relocated to another brothel" comprise the

second biggest group (23.7%).

As Kusama explains, these women did not exit prostitution but moved to or were bought by a

different brothel where they continued to work as prostitutes.

According to "Geish?gi shakufu shokaigyo ni kansuru chosa",licensed prostitutes experienced

impatience and distress and decided to move to other brothels for reasons including (1) not being

able to earn enough money, (2) debts accrued because fathers, brothers or lovers asked for money,

and (3) disadvantageous contracts that prevented them from paying down their debts. 54

年によって多少のばらつきはありましたが、「別の売春宿に転居した」 人が2番目に大きいグループ

(23.7%)を構成しています。

草間が説明するように、これらの女性は売春をやめなかったが、売春宿として働き続けた別の売春

宿に引っ越したか、売春宿に買収された。

「芸者の酌婦業に関する調査」 によると、免許を持った売春婦は、(1)お金が足りない、(2)父親、兄

弟、恋人が頼んだために借金が発生したなどの理由で、焦りと苦痛を経験し、他の売春宿に引っ越す

ことにした。

お金のために、そして(3)彼らが彼らの借金を返済することを妨げた不利な契約。 54

When a prostitute relocated of her own volition, her debt became subject to interest, which was

retroactively charged back to the date she began working.

In Osaka, a prostitute moving to another brothel was required to pay not only interest but also a

penalty.

Therefore, every time licensed prostitutes or geisha relocated, they accumulated more debt,

making an exit from the business even more remote. 55

売春婦が自分の意志で転居したとき、彼女の借金は利息の対象となり、それは彼女が働き始めた日

までさかのぼって請求されました。

大阪では、売春宿に引っ越してきた売春婦は、利子だけでなく罰金も払わなければならなかった。

したがって、認可された売春婦や芸者が移転するたびに、彼らはより多くの借金を蓄積し、事業から

の撤退をさらに遠ざけました。 55

At the same time, from the chart and Kusama's explanation, we can see it was not easy for

licensed prostitutes to quit when they wanted to and to repay their debts. Less than 20% of the

women on the survey were able to repay their debts from their earnings.

同時に、チャートと草間彌生の説明から、免許を持った売春婦が望むときに辞めて借金を返済する

のは容易ではなかったことがわかります。

調査対象の女性の20%未満が、収入から借金を返済することができました。

Kusama also writes that the biggest group across the two years were those who were released by

their owners "leniently" or onkeitekini even though they were not able to repay their advances

within the contracted terms. In other words, absent the “"eniency" of brothel owners, many

licensed prostitutes would not have been able to quit.

It was up to the owners not the women. Kusama also says, although it was "a custom of the

licensed quarters" to “roll up the contract and free [the women] when the term of the contract

ended regardless of whether their advance had been repaid",those prostitutes who had not been

able to pay back the debt when they finished the term had to give back their kimono and everything

else they had purchased while they worked to help pay their remaining debt and "were free with

nothing". 56

草間はまた、2年間で最大のグループは、契約期間内に前払い金を返済できなかったにもかかわら

ず、所有者から 「寛大に」 または恩恵的によって解放されたグループであったと書いています。

言い換えれば、売春宿の所有者の 「寛大さ」 がなければ、多くの認可された売春婦は辞めることが

できなかっただろう。

それは女性ではなく所有者次第でした。

草間彌生はまた、「 前払金が返済されたかどうかにかかわらず、契約期間が終了したときに契約を

ロールアップして解放する 」 ことは 「 認可された地区の慣習」であったが、 学期が終わったときに借

金を返済することができたのは、残りの借金を返済するために働いている間に着物や購入した他のす

べてのものを返済しなければならず、「何もなしで自由だった」。 56

Kusama writes that there must have been quite a few prostitutes "who could earn more than 10,

000 yen over six years",more than the typical advance. "Despite that",Kusama continues, "it is a

pity that they still could not repay their debts by the end of their term of service, and were only

freed from their cages through the leniency of the brothel owners". 57

In terms of "redeemed by parents",Kusama explains that debt in this category was likely actually

at least in part paid by clients.

草間彌生は、「6年間で1万円以上稼げる」 売春婦は、通常よりもかなり多かったに違いないと書いて

いる。

「 それにもかかわらず、草間は、彼らが任期の終わりまでに彼らの借金を返済することができず、売

春宿の所有者の寛大さによって彼らの檻から解放されただけであったことは残念です 」 と続けます。

57

「親が償還する」 という意味では、草間氏は、このカテゴリーの債務は、実際には少なくとも部分的に

顧客によって支払われた可能性が高いと説明しています。

These descriptions included in the materials on which Ramseyer relied go against in the argument

that licensed prostitutes could easily exit the industry.

He did not include them.

ラムザイヤーが依拠した資料に含まれているこれらの説明は、認可された売春婦が簡単に業界から

撤退する可能性があるという議論に反しています。

彼はそれらを含めませんでした。

3-5. Licensed prostitutes were able to finish paying back their debts within three years?

3-5。 認可された売春婦は3年以内に彼らの借金を返済することを終えることができましたか?

Ramseyer says that a licensed prostitute's yearly income averaged 655 yen in 1925, and considers

that high. If the women allocated 60% (393 yen) of that amount to repay their debts, he claims, they

would be able to repay a debt of 1,200 yen in about in three years.

Although there is room to question whether his estimate of a licensed prostitute’s annual income

or the amount of the advance are accurate, I am more interested in a different question.

ラムザイヤー氏によると、1925年の売春婦の年収は平均655円で、これは高いと考えている。

女性がその60%(393円)を借金返済に充てれば、約3年で1200円の借金を返済できるとのこと。

売春婦の年収の見積もりや前払金の額が正確かどうかは疑問の余地がありますが、私は別の質問

に興味があります。

Surely, there must have been some prostitutes who were lucky enough to pay back their debts in

three years.

Even if, however, they could quit working as a prostitute by paying back the debt in three years,

the central fact is that the contracts were invalid and violated various international and domestic

laws because they required them to work until the debts were repaid, as pointed out above.

確かに、3年で借金を返済するのに十分幸運だった売春婦がいたに違いありません。

しかし、3年で借金を返済することで売春婦としての仕事を辞めることができたとしても、借金が返済さ

れるまで働くことを要求されたため、契約は無効であり、さまざまな国際法および国内法に違反してい

ました。 上で指摘した。

Moreover, even if we estimate the yearly income for a licensed prostitute as he does, anyone can

see that his reasoning that they must have been able to pay back their debts in about three years

isn't well-backed by the data.

We cannot say anything unless we learn how much their expenses were.

If there was more spending than income, as some reports make clear, their debts would pile up

and they would not be able to repay.

さらに、認可された売春婦の年収を彼のように見積もっても、約3年で借金を返済できたはずだという

彼の推論はデータに裏付けられていないことがわかります。

彼らの費用がいくらだったかを知らない限り、私たちは何も言うことができません。

収入よりも支出が多ければ、いくつかの報告が明らかにしているように、彼らの借金は積み重なっ

て、彼らは返済することができません。

What is certain is that many of the women faced extraordinary difficulty in repaying the debts; for

many, the amount of debt rose as expenses outpaced earnings.

And there is no way that Ramseyer could have missed this fact, which was emphasized in the

materials that he deeply relied on for his argument.

Yet he almost completely ignores this.

確かなことは、多くの女性が借金を返済するのに非常に困難に直面したということです。

多くの人にとって、経費が収益を上回ったため、債務額は増加しました。

そして、ラムザイヤーがこの事実を見逃すことができなかったはずがありません。

それは、彼が彼の議論のために深く依存した資料で強調されていました。

しかし、彼はこれをほぼ完全に無視しています。

For example, "Geish?gi shakufu shokaigyo ni kansuru chosa" includes some cases in which their

debts increased and decreased. 58

Joky? to baishofu does as well.

Let us look at one example from the latter.

例えば、「芸者の酌婦紹介業に関する調査」 には、借金が増減する場合があります。 58

売娼婦の状況もそうです。

後者の例を見てみましょう。

In June 1917, a licensed prostitute began working at a brothel in Yoshiwara, receiving 650 yen as

an advance and an additional 139.93 yen for chokashikin or chogashikin (money lent by the owner to

pay for clothes and her futon, along with the fee for the recruiter59), which makes 789.93 yen in

total.60 At this brothel, gyoku or gyokudai (the fee for sex with a client) is one yen.

The brothel owner's share is 0.7 yen while the prostitute’s is 0.3 yen.

The total fees paid by her clients were 708 gyoku in her first five months.

Of her 212.4 yen share, she assigned 141.60 yen to the repayment of her advance.

This means that her repayment was going smoothly, but this did not last.

Since she became a licensed prostitute at the start of the summer, she had prepared only

summer kimono for work. In October she borrowed 234.3 yen to purchase winter kimono.

That increased her debt to 883.43 yen, about 93 yen more than her original advance, Kusama

notes. He says, "The brothel owner would encourage the girls to decorate themselves beautifully if

they were popular and sell a lot of gyoku". 61

1917年6月、認可された売春宿が吉原の売春宿で働き始め、前払いとして650円、長貸し金または長

ガシキン(所有者が衣服と布団の代金として貸与した金額、およびリクルーター 59)、合計789.93円。

60

この売春宿では、玉または玉台(顧客とのセックスの料金)は1円です。

売春宿の所有者のシェアは0.7円、売春婦のシェアは0.3円です。

彼女のクライアントによって支払われた合計料金は、彼女の最初の5か月で708行でした。

212.4円の株式のうち、前払金の返済に141.60円を割り当てた。

これは彼女の返済が順調に進んでいたことを意味しますが、これは長続きしませんでした。

彼女は夏の初めに認可された売春婦になったので、彼女は仕事のために夏の着物だけを準備して

いました。

10月に234.3円を借りて冬の着物を購入しました。

それは彼女の負債を883.43円に増やしました、それは彼女の最初の前払いより約93円多いと草間は

言います。

「 売春宿のオーナーは、人気があり、玉をたくさん売るなら、女の子たちに美しく飾るように勧めるだ

ろう 」 と彼は言います。 61

Fukumi also says that the debts kept piling up because many licensed prostitutes were not able to

cover necessary expenses with their allowances. Expenses included: (1) miscellaneous items like

cosmetics (2) kimono for work; (3) money for their parents; (4) sick days, and so on. He particularly

emphasized the importance of (2).

Licensed prostitutes had to change their kimono depending on the season, but few could cover

that expense with their own money.

The formalities of buying a kimono also merit attention, Fukumi says. "Prostitutes who did not

have enough money to purchase a new kimono on their own often enlisted the help of the brothel

owners. This opened them to malpractice like owners charging a 20 percent or 50 percent surcharge

or forcing prostitutes to buy what they don't want". 62

福見氏はまた、多くの認可された売春婦が彼らの手当で必要な費用を賄うことができなかったので、

借金は積み重なっていたと言います。

含まれる費用:(1)化粧品のような雑多なアイテム(2)仕事のための着物。 (3)両親のためのお金。

(4)病欠など。

彼は特に(2)の重要性を強調した。

認可された売春婦は季節に応じて着物を着替えなければなりませんでしたが、その費用を自分のお

金でまかなうことができる人はほとんどいませんでした。

着物を買う手続きも注目に値する、と福見は言う。

「 自分で新しい着物を購入するのに十分なお金がなかった売春婦は、売春宿の所有者の助けを借り

ることがよくありました。 欲しいです 」。 62

The descriptions above that emphasize how difficult it was for licensed prostitutes to repay their

debts are certainly inconvenient for Ramseyer's argument that they were able to repay their debts

about for three years.

That is why, here again, Ramseyer ignored the inconvenient facts in the materials on which he

relies.

認可された売春婦が彼らの借金を返済することがどれほど困難であったかを強調する上記の説明

は、彼らが約3年間彼らの借金を返済することができたというラムザイヤーの議論にとって確かに不便

です。

そのため、ここでも、ラムザイヤーは、彼が依存している資料の不便な事実を無視しました。

4. Conclusion

4.結論

I'd like to conclude by making the following two points.

最後に、次の2点を挙げて締めくくりたいと思います。

First of all, after checking the descriptions of licensed prostitutes in Ramseyer's "Contracting for

Sex in the Pacific War" using the materials he relies on, I find that the article does not meet the

standards of an academic article.

On the content of the licensed prostitute contract, which is the basis of his essay, Ramseyer

ignores evidence in the historical materials he supposedly relies on which reveals the deprivation of

the licensed prostitute' freedom.

He also constructs his claim in other parts of his article by ignoring numbers in the documents

that are inconvenient to his argument, neglecting provisions and making an estimate which easily

breaks down under scrutiny.

We cannot say that an article like this, regardless of its theme, meets the requirements of an

academic article.

まず、ラムザイアーの 「太平洋戦争でのセックスの契約」 の認可された売春婦の説明を彼が頼りに

している資料を使って調べたところ、その記事は学術論文の基準を満たしていないことがわかりまし

た。

彼のエッセイの基礎である認可された売春婦契約の内容に関して、ラムザイヤーは、認可された売

春婦の自由の剥奪を明らかにする彼が依存していると思われる歴史的資料の証拠を無視します。

彼はまた、彼の議論に不便な文書の数字を無視し、規定を無視し、精査の下で簡単に崩壊する見積

もりをすることによって、彼の記事の他の部分で彼の主張を構築します。

このような論文は、テーマを問わず、学術論文の要件を満たしているとは言えません。

Secondly, Ramseyer connects "licensed prostitutes" to "comfort women" by saying that both

made contracts based on mutual agreement, their own interests, and consent.

I'd like to point out that in reality the licensed prostitutes and the military "comfort" women were

related in a very different way from what Ramseyer suggests.

In the licensed prostitution system in prewar Japan, owners of brothels were able to trade

licensed prostitutes, geisha, and barmaids under state authorization.

It was this framework that enabled the Japanese military to use traders and recruit women widely

when the war started.

Japanese women who were licensed prostitutes, geisha or barmaids were sometimes forced to

become "comfort women". 63

There were also many cases in which women with no connection to licensed prostitution were

gathered through pretense or human trafficking under the direction of the Japanese Army.

第二に、ラムザイヤーは、「免許を持った売春婦」 と 「慰安婦」 を結びつけ、両者は相互の合意、彼

ら自身の利益、同意に基づいて契約を結んだと述べています。

実際には、認可された売春婦と軍の 「慰安婦」 は、ラムザイヤーが示唆しているものとは非常に異

なる方法で関係していたことを指摘したいと思います。

戦前の日本の認可された売春制度では、売春宿の所有者は、国家の許可の下で認可された売春

婦、芸者、およびバーテンダーを取引することができました。

戦争が始まったとき、日本軍が貿易業者を利用し、女性を広く採用することを可能にしたのはこの枠

組みでした。

売春婦、芸者、バーテンダーの免許を持っていた日本人女性は、「慰安婦」 になることを余儀なくされ

ることがありました。 63

また、日本軍の指揮の下、売春の許可を受けていない女性が、偽りや人身売買によって集められた

ケースも多かった。

Thus, the relationship between the "comfort women" problem and the licensed prostitution

system sheds light on the terrible discrimination in modern Japanese society against women.

The logic that "comfort women" were "licensed prostitutes" and “that's why they were not

victims” is not acceptable.

Far from it.

I have to say that this logic truly expresses an extremely low level of consciousness of human

rights as well as a catastrophic indifference to scholarly standards.

このように、「慰安婦」 問題と認可された売春制度との関係は、現代の日本社会における女性に対

するひどい差別に光を当てています。

「慰安婦」 が 「売春婦」 であり、「だからこそ犠牲者ではなかった」 という論理は受け入れられない。

それからは程遠い。

この論理は、人権に対する非常に低いレベルの意識と、学術的基準に対する壊滅的な無関心を本

当に表現していると言わざるを得ません。

《 注釈と参考文献は吉見義明氏と同様に省略 》

こちらも吉見義明氏のアレと同様に“任意売春” の定義をガチガチに固めて、その定義から外れた

例をピックアップすることで、「 彼女達を任意売春婦と決めるけることは出来ない 」 と書いてあるんで

すな。 吉見義明氏のアレと同じ典型的なストローマン手法で、ラムザイヤー氏の主張の根幹が 「 慰

安婦の正体は高額で任意契約した売春婦 」 って言っているのに、辞めたくても辞められなかったと

か、ひとつの売春宿から足抜け出来ても、また別の売春宿で働いていたとか、商売道具として綺麗な

オベベを買うので借金がなかなか減らなかったとか...そういう枝葉末節にいちゃもんを幾ら付けたっ

て、根幹の部分はビクともしませんよ。

先の吉見義明氏のアレもトンデモなく酷かったけど、コッチは比較にならない位にアレに輪を掛けて

酷いですな。

“英訳” と称しつつも、あちらこちらにローマ字が混じっていて、英語圏の人間が読んでも意味が分か

らないようになっている。 おまけに、そのローマ字に長音記号マクロンを使っているから、表示するに

も機種を選ぶ ( 機種依存文字 )。 おそらく英語圏でデフォルト設定のパソコンやタブレットで見ようと

したらと文字化けしてしまうと思う ( ホームページNinja も非対応 )。 こんなの学生が大学のレポート

で提出したら目の前で破り捨てられるレベルだぞ。 良く人前に出せたな。

先の吉見義明氏と同じだけど、慰安婦が必ずしも本人の意思ではなかったとか、辞めたくても辞めら

れなかったとか、そういうのは論点じゃねーんだよ。 そもそも人と人とが殺し合いをやってんだぞ。

召集令状を貰って 「 嫌です。 行きません。」 なんて返答が許される時代じゃなかった。 裏から手を

回して召集令状が来ないように工作できた裕福層はともなく、そうじゃない市井の人たちは、召集令状

に応じなければ周囲から酷い迫害を受けて生きて行けない地獄に落とされた時代だった。 だから慰

安婦の置かれた状況とか借金を返さないと自由になれないとかそんなのはアタリマエだのクラッカー

で、ラムザイヤーの論文に書かれた骨子はそれじゃない。

慰安婦問題の骨子は、”当時の日本軍および日本政府が慰安婦問題に於いて戦争犯罪をやらかし

たか、否か” である。 問われているのは ”日本の戦争犯罪”であり、不当な契約でもなければ、不当

な扱いでもない。

契約書が雁字搦めなのは悪いことではない。 ヤクザの示談書にありがちな [ 後から解釈次第でど

うにでも曲げられる ] 契約書ではなかったという意味でしかない。 「 契約書がキッチリと書かれている

ことが悪い 」 なんて言うのは、「 私は社会経験がゼロのおこちゃまです 」 と白状しているに等しい。

年齢がお幾つなのかは寡聞にして知らないが ( ググったら、1963年産まれらしい。 ということは皇紀

2682年の今なら58歳か59歳なワケで、さすがに恥というモノを知ろうよ、と思うよねぇ )、十代の学生な

らイザ知らず齢を重ねてそれはないだろう。

閑話休題。

慰安婦問題が女衒の問題だと言うなら、それはそれで良い。 だが、ならば、慰安婦問題に日帝軍も

日本政府も関係がない。

[ 当時は新生日本人として扱われていた朝鮮人女衒 ] と [ 当時は新生日本人として扱われていた朝

鮮人売春婦 ] との [ 契約の問題 ] というなら、それで構わない。

だ け ど 、い い ん だ な 、 そ れ で ?

当 時 の 日 帝 は 何 も 関 係 が 無 い こ と に な っ て し ま う ぞ w

「 慰安婦を酷く扱うように 」 と日帝が指導していたというならともかく、実際は 「 慰安婦を酷く扱う

な 」 とお触れを出して、慰安婦を不当に扱った慰安所の運営を取り締まっていたんだから当然だわ

な。

ちなみに、ウルトラ長文なので、誰も読まないだろうと思ってなのか、シレっと嘘が混ぜてあって草。

There were also many cases in which women with no connection

to licensed prostitution were gathered through pretense or human trafficking

under the direction of the Japanese Army.

また、日本軍の指揮の下、売春の許可を受けていない女性が、偽りや人身売買によって

集められたケースも多かった。

> 日本軍の指揮の下、売春の許可を受けていない女性が、偽りや人身売買

> 日本軍の指揮の下、売春の許可を受けていない女性が、偽りや人身売買

> 日本軍の指揮の下、売春の許可を受けていない女性が、偽りや人身売買

> 多かった。

> 多かった。

> 多かった。

偽りや人身売買が日本軍の指揮の下で行われていて、かつ、多かったと云う根拠資料を示してみ

ろ!

■ 追伸 ■

冒頭に [ 20巻|第6号| 2番 ] [ 記事ID5689 ] と在るから、これは、webサイト 『Fight for Justice 日本

軍「慰安婦」――忘却への抵抗・未来の責任』 のみに投稿された記事ではなく、何か他の書籍 ( ある

いはwrbサイト ) に載せた文章だと思うのだが、それが何なのかを知りたい。 まぁ、公開論文でない

のは確かだと思うのだが、webサイト 『Fight for Justice 日本軍「慰安婦」――忘却への抵抗・未来の

責任』 みたいなおぞましいパヨサイトがまだあるというなら叩き潰しておきたいので紹介して欲しい。

|

|

|

|