|

Blogを斬る,おまけ

2022.03.21

吉見義明さんによるラムザイヤー論文への反論(英文)がアップされました。 を斬る。

2022.03.26 反駁部分の記述を一部改正

|

|

引用元URL → https://fightforjustice.info/?p=5645 ( 魚拓 )

このページは、webサイト『Fight for Justice 日本軍「慰安婦」――忘却への抵抗・未来の責任』 が開

設された2013年08月01日時点で存在しなかったページです。

いつ追加されたのか?は、

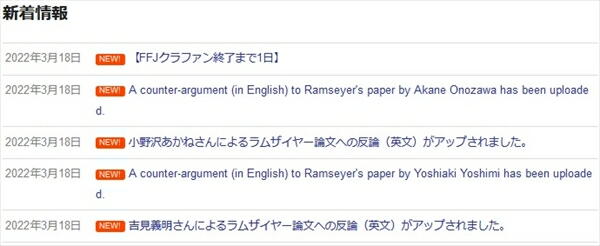

より、皇紀2682年03月18日だそうです。

では、いざ参る。

吉見義明さんによるラムザイヤー論文への反論(英文)がアップされました。

吉見義明さん(中央大学名誉教授)によるラムザイヤー論文への反論(英文)が

2月23日に以下のサイトに掲載されました。

IRLEに送った反論ですが、まずworking paperとしてSSRNにアップされました。

ご参照ください。 拡散歓迎します。

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4029325&fbclid=

IwAR3ZcUXIJwXzue3t45y1v6AEhphSkDhm5zEROR3nmLTvhxEMwCN-LvksYJY ( 魚拓 )

Response to ‘Contracting for Sex in the Pacific War’ by J. Mark Ramseyer

J・マーク・ラムザイヤーによる「太平洋戦争でのセックス契約」への回答

By Yoshiaki Yoshimi

吉見義明

Introduction

序章

would like to offer a criticism of the paper by J. Mark Ramseyer titled “Contracting for sex in the

Pacific War” that has been posted on the website of the International Review of Law and

Economics. In his introduction, Ramseyer avows that he will explore the “economic logic” of the

contractual agreements between licensed prostitutes, unlicensed prostitutes, and “comfort

women” and brothel owners6 through comparisons of contracts at brothels in Japan and in Korea,

contracts for “karayuki-san” (“overseas Japanese prostitutes”), and finally, contracts at comfort

stations.

J・マーク・ラムザイヤーの「セックスのための契約」というタイトルの論文に対する批判を申し上げた

いと思います。

International ReviewofLawのウェブサイトに掲載された 「太平洋戦争」 と経済。彼の紹介の中で、ラ

ムザイヤーは彼がの 「経済論理」 を探求することを誓います

認可された売春婦、認可されていない売春婦の間の契約上の合意、および 「快適さ日本との売春宿

での契約の比較による女性」 と売春宿の所有者 韓国、「からゆきさん」(「海外の日本の売春婦」)と契

約し、最後に慰安所。

There are, however, problems with this reasoning: (i) Ramseyer does not provide any samples of

actual contracts despite his pledge to compare them, and (ii) he presupposes the women's freely

exercised agency as they entered into contractual agreeents, which is contrary to fact.

For example, while labor and cash advance contracts for licensed prostitutes were signed by the

woman herself, her guardians (family members), as well as their guarantor (Naimush? Keihokyoku,

1931:105-154), the principal was the guardian. Since women signing on to become licensed

prostitutes were unmarried and often underage, actual contractual negotiations were conducted by

their family members.

As the 1898 Japanese Civil Code had established the ie (household) as the normative unit of the

family system, led by a head of household who exercised great authority over the family, which was

transmitted through the rule of primogeniture, the rights of daughters were severely restricted, and

they were subservient to the will of the head of household (Kano, 2007:349).

ただし、この推論には問題があります。

(i) ラムザイヤーはサンプルを提供していません。

それらを比較するという彼の誓約にもかかわらず、実際の契約の数、および

(ii) 彼は女性の彼らが契約上の合意を締結したときに自由に行使された代理店は、

事実に反しています。

たとえば、認可された売春婦のための労働と現金前貸し契約はによって署名されましたが

女性自身、彼女の保護者(家族)、そして彼らの保証人(内務省 Keihokyoku、1931:105-154)、

校長は保護者でした。

女性がサインオンしてから認可された売春婦は未婚で、しばしば未成年であり、

実際の契約交渉は彼らの家族によって行われた。

1898年の日本の民法がすなわちを確立したように(世帯)世帯主が率いる家族制度の

規範的単位として家族に対して大きな権威を行使し、

それは長子相続、娘の権利は厳しく制限され、彼らは世帯主の意志(狩野、2007:349)。

In the case of contracts for “comfort women,” for example, on January 19th, 1938, brothel owner

Ouchi Toshichi of Kobe paid two women working at a restaurant (de facto brothel) in Mito 642 yen

and 691 yen respectively as advances and sent them to a military comfort station in Shanghai

(NaimushoKeihokyokucho,1938).

No contracts have been discovered, but since such women typically owed the restaurant for

advances they had received, and in turn were valued “assets” to the restaurant, it is likelythat the

owner of the restaurant negotiated with the recruiter and received most of the advances. It is

simply a fiction that women exercised their freedom in contracting to become prostitutes.

Furthermore, (iii) contracts for licensed prostitution, unlicensed prostitution, and "comfort women"

were agreements to repay loans through prostitution, and as such should be noted as a form of

human trafficking and not legitimate contracts in ordinary civil society.

I intend to explore point (iii) further in the main portion of this article, but Ramseyer’s argument

collapses based on these three points alone.

たとえば、1938年1月19日、「慰安婦」の契約の場合、神戸の売春宿のオーナーである大内東七は、

水戸のレストラン(事実上の売春宿)で働く女性2人に、それぞれ642円と691円の前払い金を支払って

送金しました。彼らは上海の軍の慰安所に向かった(Naimush?Keihokyokuch?、1938)。

契約は発見されていませんが、そのような女性は通常レストランに借りがあるので彼らが受け取った

前払金については、レストランの「資産」として評価され、レストランの所有者は採用担当者と交渉し、

ほとんどの前払金を受け取った可能性があります。

女性が売春婦になるために契約する自由を行使したのは単なるフィクションです。

さらに、(iii)認可された売春、認可されていない売春、および「慰安婦」は売春を通じてローンを返済

する合意であり、それ自体は人身売買の一形態であり、通常の市民社会における合法的な契約では

ないことに注意する必要があります。

この記事の主要部分でポイント(iii)をさらに探求するつもりですが、ラムザイヤーの議論はこれら3つ

のポイントだけに基づいて崩壊します。

1. Japan’s licensed prostitution system

1.日本の認可された売春制度

1-1 Contemporary Legal Issues

1−1 一時的な法的問題

As mentioned previously, Ramseyer ignores such facts as contracts between women who would

become prostitutes and brothel owners were negotiated between women's guardians and the brothel

owners, or that these contracts entailed women paying off advances handed over to their guardians

through prostitution, and hence precipitated enslavement of the trafficked women.

This is astonishing If such contracts forced any woman to engage in prostitution even for a day,

that by itself would constitute a serious violation of her human rights.

前に述べたように、ラムザイヤーは女性間の契約などの事実を無視します

売春婦になり、売春宿の所有者は女性の保護者と売春宿の所有者、またはこれらの契約は女性が

に引き渡された前払い金を支払うことを伴うこと

売春を通じて彼らの保護者、したがって人身売買された人身売買の奴隷化を促進した

女性。そのような契約が女性に売春に従事することを強制した場合、これは驚くべきことです

一日の間、それ自体が彼女の人権の重大な侵害を構成するでしょう。

These illegal contracts were openly entered into in Japan and in Korea at the time because the

Japanese Government tolerated them.

Under Article 224 of the Penal Code in effect in Japan and Korea, anyone found guilty of

kidnapping7 minors could be sentenced to penal servitude ranging from three months to five years.

Article 225 of the Code also stipulated that someone found guilty of kidnapping a person for the

purposes of exploitation, acts of indecency, or marriage, faced penal servitude of one to ten years,

but there were no sanctions against human trafficking per se. Article 226 nominally established the

crime of human trafficking for the purpose of transporting the victim overseas, which prohibited

kidnapping or trafficking of another person and transporting him or her outside of Japan and its

colonies.

In other words,human trafficking within Japan and its colonies was not criminally prosecuted. Only

after facing intense criticism from the U.S.

Department of State and others within and outside Japan for its apparent tolerance of human

trafficking, Japan amended the Code in 2005 by adding a clause prohibiting domestic and inbound

human trafficking.

これらの違法契約は、当時、日本と韓国で公然と締結されていました。

日本政府はそれらを容認しました。日本で施行されている刑法第224条に基づく

そして韓国では、7人の未成年者を誘拐した罪で有罪となった人は誰でも懲役刑を宣告される可能性

があります

3ヶ月から5年の範囲。規範の第225条は、誰かが搾取、猥褻行為、または結婚、1年から10年の懲役

に直面したが、人間に対する制裁はなかった人身売買それ自体。

第226条は、名目上、人身売買の犯罪を立証しました。

誘拐や人身売買を禁止した犠牲者を海外に輸送する目的別の人と彼または彼女を日本とその植民

地の外に輸送する。

言い換えると、日本とその植民地内での人身売買は刑事訴追されませんでした。

直面した後のみ米国国務省をはじめとする国内外からの激しい批判人身売買の見かけの許容度、

日本は条項を追加することにより2005年にコードを修正しました

国内およびインバウンドの人身売買を禁止する。

Legally binding agreements whose aims were contrary to public order and morals were deemed

void under Article 90 of the Civil Code.

Contracts requiring women to pay back their advances through prostitution should have been

voided under this clause, and women seeking to exit prostitution petitioned the Courts to have their

contracts voided, with the assistance of activists against licensed prostitution. But the Courts

tended to divide the contracts into two distinct aspects, ruling the agreement for prostitution labor

illegal and void, while upholding the legality of the loan itself, ordering the prostitutes to repay their

advances (Maki, 1971:217-218), leaving the women under the control of the brothels and unable to

exit. The Supreme Court of Japan finally declared the entire contract void and relieved such

women from financial obligations in 1955, after the end of the World War II.

Japanese courts have thus permitted such illegal contracts for many years.

公序良俗に反する目的の法的拘束力のある協定は、民法第90条に基づいて無効とみなされました。

女性に売春を通じて前払い金を返済することを要求する契約はこの条項の下で無効にされるべきで

あり、売春を終了しようとする女性は、認可された売春に対する活動家の助けを借りて、契約を無効に

するよう裁判所に請願した。

しかし、裁判所は契約を2つの異なるものに分割する傾向がありました

側面、売春労働の合意を違法かつ無効に裁定し、ローン自体の合法性を支持し、売春婦に前払い

金の返済を命じ(Maki、1971:217-218)、女性を売春宿の管理下に置き、出口。

日本の最高裁判所は、第二次世界大戦の終結後の1955年に、最終的に契約全体を無効と宣言し、

そのような女性を財政的義務から解放しました。

したがって、日本の裁判所は、長年にわたってそのような違法な契約を許可してきました。

Ramseyer mentions the existence of recruiters, who were called zegen (meaning traders of

women) and facilitated human trafficking.

Ramseyer stresses that Korea in particular had "a large corps of professional labor recruiters"

with "a history of deceptive tactics" (p.5), but there were many of them in Japan as well.

These recruiters were sanctioned by the Home Ministry in Japan, and by the Governor-General of

Korea. In 1931, the League of Nations dispatched a delegation from the Commission of Enquiry into

Traffic in Women and Children in the East to survey China, Korea, Japan, and other areas. It issued

a report in 1933 criticizing the Japanese government's formal sanctioning of recruiters for the

operation of brothels, but the Japanese government did not follow through by prohibiting such

recruiters (Onozawa, 2010:225-226).

After total war broke out between Japan and China in 1937, the Japanese government prohibited

private labor recruiters in 1938 to control and mobilize the labor force, but did not ban recruitment

for prostitution.

During the war, these recruiters were enlisted by the government and the military to round up "

comfort women" to serve members of the military as well as the workers of munitions factories.

Private recruiters for prostitution were not prohibited until 1947, after Japan had lost the war

(Yoshimi, 2019:150-151,231).

ラムザイヤーは、ゼゲン(女性の商人を意味する)と呼ばれ、人身売買を促進したリクルーターの存

在に言及しています。

ラムザイアーは、特に韓国には「欺瞞的な戦術の歴史」(p.5)を備えた「プロの労働者採用者の大規

模な軍団」があったと強調しているが、日本にも多くの人がいた。

これらの採用担当者は、日本の内務省と韓国総督によって認可されました。 1931年、国際連盟は、

調査委員会から東部の女性と子どもの交通に関する代表団を派遣し、中国、韓国、日本、およびその

他の地域を調査しました。 1933年に、日本政府が売春宿の運営について採用担当者を正式に制裁し

たことを批判する報告書を発行したが、日本政府はそのような採用担当者を禁止することはしなかっ

た(Onozawa、2010:225-226)。

1937年に日中戦争が勃発した後、日本政府は1938年に民間の労働者採用者が労働力を管理し動

員することを禁止したが、売春のための採用を禁止しなかった。

戦争中、これらの採用担当者は、軍隊のメンバーと軍需工場の労働者に奉仕するために「慰安婦」

をまとめるために政府と軍隊に参加しました。

日本が戦争に敗れた後の1947年まで、売春のための民間のリクルーターは禁止されなかった

(Yoshimi、2019:150-151,231)。

1-2 Conditions facing women in brothels

1-2 売春宿で女性が直面している状況

Ramseyer also ignores the real conditions of women living in brothels. First, prostitutes were

required to live within a designated area.

There were no rules requiring them to live in a specific brothel, but since they had nowhere else to

live, they were forced to live and to prostitute on the property of the brothel owned by their

purchasers. Superintendent of the Metropolitan Police Department Fukumi Takao wrote that these

women who lacked freedom of residence were "like slaves belonging to the brothel owner" (Fukumi,

1928:50).

ラムザイヤーはまた、売春宿に住む女性の実際の状況を無視しています。まず、売春婦は指定され

た地域に住む必要がありました。

特定の売春宿に住むことを要求する規則はありませんでしたが、他に住む場所がなかったため、購

入者が所有する売春宿の所有物を売春することを余儀なくされました。副見喬警視庁長官は、居住の

自由を欠いたこれらの女性は「売春宿の所有者に属する奴隷のようだった」と書いている(副見喬、

1928:50)。

Ramseyer argues that prostitutes “could easily leave their brothels and disappear into the

anonymous urban environment” (p.2), but this is incorrect.

If it were true, most prostitutes in urban areas would have escaped, and the system of licensed

prostitution would have collapsed immediately. In reality, prostitutes were required to receive

permission from the police in order to leave the premises (Article 7, Regulatory Rules on Licensed

Prostitutes), and had to be accompanied by a warden even with such permission (i.e., deprivation of

the freedom of movement).

This regulation was abolished in 1933 in response to demands made by anti-prostitution activists,

but brothel owners continued to interfere with the free movement of the prostitutes.

Whenever a woman ran away, brothel owners cooperated with the police to chase after her.

Recruiters were obligated to go after runaway prostitutes, and escape was seldom successful.

ラムザイヤーは、売春婦は「売春宿を簡単に離れて、匿名の都市環境に姿を消すことができる」と主

張しているが(p.2)、これは正しくない。

もしそれが本当なら、都市部のほとんどの売春婦は逃げ出し、認可された売春婦のシステムはすぐ

に崩壊したでしょう。現実には、売春婦は敷地を離れるために警察から許可を得る必要があり(第7

条、認可された売春婦に関する規制規則)、そのような許可があっても監視員を同伴しなければなりま

せんでした(すなわち、移動の自由の剥奪)。

この規制は、売春反対活動家からの要求に応えて1933年に廃止されましたが、売春宿の所有者は

売春婦の自由な移動を妨害し続けました。

女性が逃げるたびに、売春宿の所有者は警察に協力して追跡しました

彼女の後。

採用担当者は暴走した売春婦を追いかける義務があり、脱出はめったに成功しませんでした。

Further, prostitutes were unable to exit the trade unless they had completely repaid their debt,or

after they had served the required number of years as determined by each prefecture.

Ramseyer argues that prostitutes could leave after repaying their debt in three years (p.2), but

even if that were true, the women were deprived of their liberty for three years and kept under the

control of the brothel owner for their profit.

Freedom to leave must mean the freedom to stop engaging in prostitution at any time a woman

wished to do so, but these women had no such freedom.

さらに、売春婦は、借金を全額返済しない限り、または各県が定めた必要な年数を務めた後、取引

を終了することができませんでした。

ラムザイヤーは、売春婦は3年以内に借金を返済した後に去ることができると主張しているが(p.2)、

それが真実であったとしても、女性は3年間自由を奪われ、利益のために売春婦の所有者の管理下に

置かれた。

去る自由とは、女性が望むときにいつでも売春をやめる自由を意味しなければなりませんが、これら

の女性にはそのような自由がありませんでした。

In addition, women did not have the freedom to choose their customers or to refuse to engage in

prostitution.

A participant at the national meeting of chiefs of prefectural police in 1926 opined that "the

current law subjects prostitutes to absolute obedience, but in the interest of protecting human

rights, the law should be drastically amended to allow prostitutes to choose their customers" (Asahi

Shimbun, May 4, 1926).

The right to refuse prostitution was not even considered at the meeting.

In other words, there was no freedom to refuse prostitution.

Moreover, periodic medical checkups for venereal disease that were mandated (Article 9,

Regulatory Rules on Prostitutes) also constituted a grave human rights violation.

さらに、女性には顧客を選ぶ自由や売春を拒否する自由がありませんでした。

1926年の県警長官会の参加者は、「現行法は売春婦を絶対服従させるが、人権を守るために、売春

婦が顧客を選べるように法を大幅に改正すべきだ」と述べた(朝日新聞)。新聞、1926年5月4日)。

売春を拒否する権利は会議でさえ考慮されませんでした。

言い換えれば、売春を拒否する自由はありませんでした。

さらに、義務付けられた性感染症の定期健康診断(第9条、売春婦に関する規制規則)も重大な人権

侵害を構成しました。

Article 1 of the 1926 Convention to Suppress the Slave Trade and Slavery defined slavery as "

the status or condition of a person over whom any or all of the powers attaching to the right of

ownership is exercised".

The essence of slavery under this definition is understood to mean "control over a person, and

that control means the deprivation of one's freedom or agency in a considerable way” (Abe, 2015:

32, 37).

The definition under this convention includes not just formal systems of slavery, but also de facto

slavery (i.e., the condition of enslavement).

奴隷貿易と奴隷制を抑圧する1926年の条約の第1条は、奴隷制を 「所有権に付随する権限のいず

れかまたはすべてが行使される人の地位または状態」 と定義しました。

この定義の下での奴隷制の本質は、「人を支配することを意味し、その支配は、かなりの方法で人の

自由または主体性を奪うことを意味する」と理解されています(阿部、2015:32、37)。

この条約の下での定義には、正式な奴隷制のシステムだけでなく、事実上の奴隷制(すなわち、奴隷

制の条件)も含まれます。

According to this definition, the system of licensed prostitution that deprives such basic rights as

freedom of residence, of movement, of exit; of agency in selecting customers or refusing to

prostitute; and mandates compulsory medical checkups for venereal disease, must be recognized as

a system of slavery, or sexual slavery.

During the 1920s and 1930s, the anti-licensed prostitution movement in Japan successfully

promoted the recognition that the "system of licensed prostitution was a form of de facto slavery

based on the twin evils of human trafficking and the deprivation of liberty".

Between 1928 and 1942, twenty-one prefectural assemblies passed resolutions calling for an end

to the system of licensed prostitution. Of these, Kanagawa (1930), Miyazaki (1932), and Kagoshima

(1937) Prefectures incorporated the statement quoted above in their resolutions. In national politics,

parliamentary representatives Hoshijima Niro, Abe Isoo, Nagai Ryutaro, and Wakatsuki Reijiro-who

twice served as the Prime Minister-spoke out against the system of licensed prostitution as a form

of slavery (Onozawa, 2015:7).

この定義によれば、居住、移動、退去の自由などの基本的権利を奪う認可された売春のシステム。

顧客の選択または売春の拒否における代理店の性病の強制健康診断を義務付けており、奴隷制また

は性的奴隷制として認識されなければなりません。

1920年代から1930年代にかけて、日本の売春反対運動は、「売春の制度は、人身売買と自由の剥

奪という2つの悪に基づく事実上の奴隷制の一形態である」という認識を広めることに成功した。

1928年から1942年の間に、21の都道府県議会が、認可された売春制度の廃止を求める決議を可決

した。このうち、神奈川県(1930)、宮崎県(1932)、鹿児島県(1937)は、上記の声明を決議に盛り込ん

だ。国政では、首相を二度務めた星島二郎、安部磯、永井柳太郎、若槻稔郎が奴隷制としての売春

制度に反対した(小野沢、2015:7)。

By 1935, even the Police Affairs Bureau of the Home Ministry acknowledged the system of

licensed prostitution as de facto slavery, noting that "it is an extreme affront to our intrinsic

national character to tolerate licensed prostitutes that are akin to slaves".

The Bureau based this understanding on findings that (i) prostitutes lived on brothel premises and

were made to work within the designated area; (ii) prostitutes' "life course and career were under

the surveillance of the brothel owner"; (iii) prostitutes not only lacked the freedom to choose their

customers, but they were forced to engage in prostitution even when they were ill; and (iv) all such

acts of prostitution were effectively under the control of the brothel owner, with "most profits from

prostitution benefiting the owne"r, and prostitutes "never in the condition to exercise autonomy in

the economic transaction of prostitution" (Naimusho Keihokyoku,1935:107-109).

Their perception was correct.

1935年までに、内務省の警察局でさえ、認可された売春のシステムを事実上の奴隷制として認め、

「奴隷に似た認可された売春婦を容認することは、私たちの本質的な国民性に対する極端な侮辱であ

る」と述べた。

局はこの理解を次の発見に基づいた。(i)売春婦は売春宿の敷地内に住んでおり、指定された地域

内で働かされた。 (ii)売春婦の「ライフコースとキャリアは売春宿の所有者の監視下にあった」。 (iii)売

春婦は、顧客を選ぶ自由がなかっただけでなく、病気のときでさえ売春に従事することを余儀なくされ

た。 (iv)そのような売春行為はすべて、事実上売春婦の所有者の管理下にあり、「売春からの利益の

ほとんどは所有者に利益をもたらす」rであり、売春婦は「売春の経済的取引において自治権を行使す

る状態にない」(Naimush?娼婦曲、1935:107-109)。

彼らの認識は正しかった。

Kawashima Takeyoshi, then a professor at the University of Tokyo and an authority on the

Japanese Civil Code, also considered contractual relationships under the system of licensed

prostitution as one between a slave and a slave holder, clearly stating:

当時東京大学の教授であり、日本の民法の権威であった川島武宜も、認可された売春制度の下で

の契約関係を奴隷と奴隷所有者の間の関係と見なし、次のように明確に述べた。

The first legal problem is the power of control over another person.

As previously shown, the relationship between prostitutes and brothel owners is that of someone

who was bought and one who bought, or a slave and a slave holder.

Prostitutes would try to avoid forced labor or escape, and brothel owners would use a variety of

means to enforce labor, control the bodies of workers, and chase after and detain women who

escaped.

Regrettably, these illegal acts of brothel owners in violation of basic human rights had been allowed

to continue effectively for a long time. (Kawashima, 1951:708-709).

最初の法的な問題は、他の人を支配する力です。

前に示したように、売春宿と売春宿の所有者の関係は、購入した人と購入した人、または奴隷と奴隷

所有者の関係です。

売春婦は強制労働や逃亡を避けようとし、売春宿の所有者はさまざまな手段を使って労働を強制し、

労働者の体を管理し、逃亡した女性を追いかけて拘留します。

残念ながら、これらの売春宿所有者の基本的人権を侵害する違法行為は、長期間にわたって効果

的に継続することが許されていました。 (川島、1951:708-709)。

Ramseyer is neglecting the very serious human rights violation wherein prostitutes were placed in

the condition of enslavement.

ラムザイヤーは、売春婦が奴隷化の状態に置かれたという非常に深刻な人権侵害を無視していま

す。

2. Licensed prostitution in Korea

2.韓国で認可された売春

Ramseyer’s paper also presumes, without examining the problem of human trafficking or the

reality of the system of licensed prostitution, contracts for licensed prostitution in Korea to be

agreements freely entered between women and the brothel owner.

That is dubious.

Human trafficking was a serious violation of women’s human rights in Korea, and the system of

licensed prostitution in Korea was a form of slavery just as it was in Japan.

ラムゼイヤーの論文はまた、人身売買の問題や売春の認可制度の現実を検討することなく、韓国で

の売春の認可契約は、女性と売春宿の所有者との間で自由に締結された協定であると推定している。

それは疑わしいです。

人身売買は韓国における女性の人権の重大な侵害であり、韓国における売春の認可制度は、日本

と同様に奴隷制の一形態でした。

That is, licensed prostitutes in Korea were also deprived of their freedom of residence, of

movement, of exit; of agency to refuse customers; and were subject to involuntary examinations for

venereal disease.

Further, the Korean system of licensed prostitution had additional problems that were different

from that of Japan: the minimum age requirement for licensed prostitutes was seventeen years, one

year younger than in Japan (as Ramseyer also mentions).

Freedom to exit prostitution was not established as a right belonging to the prostitute, but instead

only implied under Article 7, Section 17 of the Korean Regulatory Rules on Brothels and Licensed

Prostitutes, which stated brothel owners shall not "excessively interfere with prostitutes' contracts,

exit, communication, and meetings, or use another party to do so" (Suzuki et al., 2006:621; Kim and

Kim, 2018:18).

Because of this, it was virtually impossible for prostitutes to exit the trade in Korea.

The requirement to receive a police permit in order to leave the premises of the brothel under the

Japanese Regulatory Rules on Licensed Prostitutes was abolished in 1933, but a similar clause in

the Korean equivalent was never repealed.

つまり、韓国で認可された売春婦もまた、居住、移動、退去の自由を奪われた。

顧客を拒否する代理店の;性感染症の非自発的検査を受けました。

さらに、韓国の認可売春制度には、日本とは異なる追加の問題がありました。

認可売春婦の最低年齢要件は、日本より1歳若い17歳でした(ラムザイヤーも言及しています)。

売春を終了する自由は、売春婦に属する権利として確立されたのではなく、売春宿の所有者が「売春

宿の契約を過度に妨害してはならない」と述べた売春宿および認可売春宿に関する韓国規制規則の

第7条第17項に基づいてのみ暗示されています。

退出、コミュニケーション、会議、または他の当事者を使用してそうする」(Suzuki et al。、2006:621;

Kim and Kim、2018:18)。

このため、売春婦が韓国での貿易から撤退することは事実上不可能でした。

日本の売春宿規制規則に基づく売春宿の敷地を離れるために警察の許可を得るという要件は1933

年に廃止されたが、韓国の同等の条項の同様の条項は廃止されなかった。

Ramseyer states that the problem with Korea was the presence of a great many recruiters (p.5).

But this was not only the case in Korea, but within the Japanese metropole, Taiwan, and the parts

of Manchuria controlled by Japan.

ラムザイヤーは、韓国の問題は非常に多くのリクルーターの存在であったと述べています(p.5)。

しかし、これは韓国だけでなく、日本の大都市圏、台湾、そして日本が支配する満洲の一部でも当て

はまりました。

3. "Karayuki-san"

3.「からゆきさん」

As for the so-called "karayuki-san", Ramseyer writes that "as Japanese businessmen moved for

abroad for work, young women followed" who "worked as prostitutes for the Japanese clientele,"

but this is highly inaccurate. By 1920, Japanese prostitutes working abroad numbered 8,807 women,

including 4,967 in China, 1,136 in Singapore, 1,083 in Batavia, 546 in Siberia, 246 in Hong Kong, 193 in

Calcutta, 144 in Haiphong, and 142 in Bombay, but with the exception of the women in China, "

karayuki-san" primarily catered to non-Japanese men.

Because of this, the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs decided to discourage prostitutes who

catered to "foreigners [Chinese or Southeast Asians] of the lower class" and promoted exit and

repatriation of "karayuki-san" outside of China during the 1920s. (Yoshimi, 2019: 124-132)

いわゆる 「からゆきさん」 については、ラムザイアーは 「日本人のビジネスマンが海外に出勤するに

つれて、若い女性が続いた」と書いているが、「日本人の顧客の売春婦として働いていた」が、これは

非常に不正確である。1920年までに、日本人海外で働く売春婦は、中国で4,967人、シンガポールで1,

136人、バタビアで1,083人、シベリアで546人、香港で246人、カルカッタで193人、ハイフォンで144人、

ボンベイで142人を含む、8,807人の女性でした。中国、「からゆきさん」は主に外国人男性を対象として

います。

このため、外務省は、1920年代に「下層階級の外国人(中国人または東南アジア人)」に仕える売春

婦をやめさせ、「からゆきさん」の中国国外への出国と本国送還を促進することを決定した。 (吉見、

2019:124-132)

Further, Ramseyer states that "karayuki-san" "earned generally higher wages than they could

earn within Japan", but the source he cites, page 451 of Park Yu-ha’s Teikoku no Ianfu (Comfort

Women of the Empire) is non-existent (the book only has 324 pages of main text).

It is a claim unsubstantiated by evidence. Citation errors such as this are numerous throughout

Ramseyer’s article, primary responsibility for which lies with the author of course,but also indicate a

failure of peer review process in publishing this piece.

さらに、ラムザイヤーは「からゆきさん」は「日本国内で稼ぐことができるよりも一般的に高い賃金を稼

いだ」と述べているが、彼が引用している出典、朴裕河の帝国の慰安所の451ページは存在しない。

(この本には324ページの本文しかありません)。

それは証拠によって立証されていない主張です。このような引用エラーは、ラムザイアーの記事全体

に多数あり、その主な責任はもちろん著者にありますが、この記事の公開における査読プロセスの失

敗も示しています。

Ramseyer cites the testimony of Osaki from Sandakan Hachiban Sh?kan (Sandankan Brothel No.8)

by Yamazaki Tomoko next.8 On her being sold for 300-yen advance, Ramseyer claims that "the

recruiter did not try to trick her" and that "even at age 10, she knew what the job entailed", but

this rendering is untrue. In reality, the contract was not signed between the recruiter and Osaki, but

between the brothel owner and Osaki's elder brother (Yamazaki,1972:74).

Osaki, who was in truth taken at age nine instead of ten9, made the decision to go along with the

brothel owner after they told her, "If you go to work abroad, every day is like a festival, you can

wear nice kimono, and every day you can eat as much white rice as you want".

So when Osaki was told to take customers at age thirteen, she resisted, protesting "You brought

us here when we were little without ever mentioning that kind of work, and now you tell us to take

customers. You liar!" (ibid., 90).

And after she was forced to sleep with a customer for the first time, she found it unbearable and

said, "It was so horrible, we could hardly believe it" (Ibid., 92).

She painfully recalled later, "No matter how accustomed I had become to this work, once or twice

a month I hated taking customers so much I thought I would rather die. There were times when I

would break down and cry, wondering what sort of karma I had brought upon myself that forced me

into this role" (ibid., 100).

Ramseyer’s claims such as "the recruiter did not try to trick her" or that "even at age 10, she

knew what the job entailed" are pure fabrication.

ラムザイヤーは、山崎朋子によるサンダカン八番商館(サンダカンブロテルNo.8)の大崎の証言を引

用している8。

「10歳のとき、彼女は仕事の内容を知っていました」 が、この表現は真実ではありません。

実際には、契約は採用担当者と大崎の間ではなく、売春宿の所有者と大崎の兄の間で締結されまし

た(山崎、1972:74)。

実はten9ではなく9歳で連れて行かれた大崎は、「海外で働くなら、毎日がお祭りのようで、素敵な着

物を着ることができる」と言って、売春宿のオーナーと一緒に行くことにしました。

「そして毎日、好きなだけ白米を食べることができます。」

そこで大崎は13歳で客を連れて行くように言われたとき、「そんな仕事は言わずに小さい頃にここに

連れてきてくれたのに、今は客を連れて行くように言われた。うそつきだ!」 と抵抗した。 (同上、90)。

そして、初めて客と一緒に寝ることを余儀なくされた後、彼女はそれが耐えられないことに気づき、

「それはとてもひどいので、私たちはそれを信じることができなかった 」 と言いました(同上、92)。

後で痛々しいほど思い出しました。

「 この仕事にどんなに慣れていても、月に1、2回は客を連れて行くのが嫌だったので、死にたいと思

っていました。 私が自分自身にもたらしたカルマは、私をこの役割に追いやった 」(同上、100)。

「 採用担当者は彼女をだまそうとしなかった 」 または 「 10歳のときでさえ、彼女は仕事が何を伴うか

を知っていた 」 などのラムザイヤーの主張は純粋な捏造です。

Ramseyer selectively quotes Osaki and states "If she worked hard, she found that she could

repay about 100 yen a month", but fails to mention that the repayment of the loan was not easy.

Osaki said, "Even though I worked hard without discriminating among customers and paid back one

hundred yen a month, the interest on my loan kept adding up. Things just didn't work the way I had

hoped" (Yamazaki, 1972:95, 97).

These and other important testimonies are missing from Ramseyer’s summary.

ラムザイヤーは大崎を厳選して引用し、「頑張れば月に約100円返済できることがわかった」と述べて

いるが、返済が容易ではなかったとは述べていない。

大崎氏は、「お客さんを区別せずに頑張って月に100円返済したのに、ローンの利子が増え続けた。

思った通りにいかなかった」(山崎、1972:95、 97)。

これらおよびその他の重要な証言は、ラムザイヤーの要約から欠落しています。

Ramseyer also writes that after the death of the brothel owner, Osaki was transferred to another

brothel in Singapore, but Osaki "bought a ticket back to Malaysia" (British Northern Borneo to be

more accurate, as Malaysia did not exist at the time).

But it was actually the owner’s widow who moved to Singapore, not Osaki. Osaki was actually sold

to Jesselton, then again to Tawau, from where Osaki escaped back to Sandakan (Yamazaki, 1972:104

-105).

By describing Osaki as having “found herself transferred” to another brothel without explaining

how she got there, Ramseyer obfuscates the important fact that she was sold and then resold.

ラムゼイヤーはまた、売春宿の所有者の死後、大崎はシンガポールの別の売春宿に移されたが、大

崎は 「 マレーシアへの切符を買い戻した 」 と書いている(当時マレーシアは存在しなかったので、より

正確には英国北部ボルネオ)。

しかし、実際にシンガポールに引っ越したのは、大崎ではなく、所有者の未亡人でした。大崎は実際

にジェッセルトンに売却され、その後再びタワウに売却され、そこから大崎はサンダカンに戻った(山

崎、1972:104-105)。

ラムザイヤーは、大崎がどのようにしてそこにたどり着いたかを説明せずに、別の売春宿に「自分が

転勤した」と説明することで、彼女が売られて転売されたという重要な事実を曖昧にします。

Referring to Osaki's escape to Sandakan, Ramseyer argues that "even overseas, women who

disliked their jobs at a brothel could?and did?simply disappear", but this too is contrary to Osaki's

testimony.

After realizing that she would certainly be caught if she returned to Sandakan, she and her fellow

escapees asked Okuni, one of the brothel madams in Sandakan, to intervene.

Okuni negotiated a settlement in which (i) one of the three escapees would return to Tawau, and

(ii) pay two hundred yen each for the other two to work in Sandakan (Yamazaki, 1972: 107-109).

Ramseyer's assertion that the women "could-and did-simply disappear" is thus also a fabrication.

ラムザイヤーは、大崎のサンダカンへの脱出について、「 海外でも、売春宿での仕事を嫌った女性

は、単に姿を消すことができた 」 と主張しているが、これも大崎の証言に反している。

彼女がサンダカンに戻ったらきっと捕まるだろうと気づいた後、彼女と彼女の仲間の逃亡者は、サン

ダカンの売春宿のマダムの一人である奥国に介入するように頼んだ。

出雲阿国は、(i)3人の逃亡者のうちの1人がタワウに戻り、(ii)他の2人がサンダカンで働くためにそ

れぞれ200円を支払う(Yamazaki、1972:107-109)。

したがって、女性が 「 単に姿を消すことができた、そして実際に消えた 」 というラムザイヤーの主張

もまた、捏造である。

To summarize,

(i) the contract that led to Osaki's being sent overseas was not signed by the nine-year old Osaki,

but by her older brother;

and (ii) this contract was criminal in nature,involving kidnapping and human trafficking for the

purpose of transporting the victim overseas.

Such significant problems must not be distorted.

要約すると、

(i) 大崎が海外に送られることになった契約は、9歳の大崎ではなく、

彼女の兄によって署名されました。

(ii) この契約は本質的に犯罪であり、

被害者を海外に移送する目的での誘拐と人身売買が含まれていました。

そのような重大な問題は歪められてはなりません。

4. Military comfort stations

4.軍の慰安所

4-1 The 1938 Home Ministry directive

4-1 1938年の内務省指令

Ramseyer introduces a February 23rd, 1938 directive issued by the director of the Home Ministry'

s Police Affairs Bureau (p.5).

This well-known document presents the decision of the Home Ministry, in consultation with the

Ministry of the Army, to permit travel by "comfort women" to central and northern China.

They had been recruited by agents at the request of the Army units dispatched to China.

But Ramseyer does not seem to realize that this document gave conditional approval to human

trafficking?that is, its decision to exempt the transport of women who were (i) over the age of

twenty-one, (ii) already involved in prostitution, and (iii) free from venereal disease across national

borders from the law prohibiting human trafficking for the purpose of transporting the victim

overseas, was a major violation of human rights.

ラムザイヤーは、内務省の警察局長が発行した1938年2月23日の指令を紹介します(p.5)。

この有名な文書は、陸軍省と協議して、「慰安婦」 による中国中部および北部への旅行を許可すると

いう内務省の決定を示しています。

彼らは中国に派遣された陸軍部隊の要請でエージェントによって採用された。

しかし、ラムゼイヤーは、この文書が人身売買に条件付きの承認を与えたこと、つまり、(i)21歳以

上、(ii)すでに売春に関与している、および(iii)被害者を海外に輸送する目的で人身売買を禁止する法

律から国境を越えて性病がないことは、人権の重大な侵害であった。

Moreover, Ramseyer is indifferent to the fact that similar instructions placing these three

conditions for transporting "comfort women" overseas for the purpose of prostitution were never

issued for Korea and Taiwan, making it possible for women under twenty-one as well as those

without a history of prostitution to be trafficked from Korea and Taiwan to war zones.

さらに、ラムゼイヤーは、売春目的で 「慰安婦」 を海外に輸送するためのこれら3つの条件を定めた

同様の指示が韓国と台湾に対して発行されなかったという事実に無関心であり、21歳未満の女性とそ

うでない女性を可能にします。

韓国と台湾から戦争地帯に人身売買される売春の歴史。

In parts of the document that Ramseyer chooses not to discuss, the Home Ministry directed the

Metropolitan Police Department and prefectural police departments to rigorously crack down on

recruiters who did not have a legitimate permit or a certification issued by overseas diplomatic

establishments, and those who publicized that they were "working with the understanding of the

military or in communication with the military" (Yoshimi ed., 1995:103-104).

That is to say, the Home Ministry attempted to conceal the involvement of the military in the

recruitment of military "comfort women", despite the fact that recruiters for the military "comfort

women" had to receive permission from the military (or diplomatic establishments) in order to

operate.

Ramseyer ignores this grave issue.

ラムゼイヤーが議論しないことを選択した文書の一部で、内務省は、警視庁と県警察に、合法的な

許可または海外の外交機関によって発行された証明書を持っていない採用担当者、および公表した

採用担当者を厳しく取り締まるように指示しました彼らは「軍隊の理解を持って、あるいは軍隊と連絡

を取り合って働いていた」(吉見編、1995:103-104)。

つまり、内務省は、軍の 「慰安婦」 の採用担当者が軍(または外交機関)から許可を得なければなら

なかったにもかかわらず、軍の 「慰安婦」 の採用への軍の関与を隠そうとした。

動作するために。

ラムザイヤーはこの重大な問題を無視しています。

Another point Ramseyer fails to note is that the February 23rd document was coupled with

another set of instructions issued by an adjunct in the Ministry of the Army on March 4th.

In this document, the Ministry of the Army notified Chiefs of Staff of its Northern China Area

Army and Central China Expeditionary Army that the Expeditionary Army was designated to

manage the recruitment of "women working at comfort stations", to carefully vet recruiters, and

coordinate closely with local civilian and military police for any such recruitment (Yoshimi ed.,1995:

105-106).

Hence, recruiters did not operate independently to recruit "comfort women";they had to be

vetted and selected by the military, and therefore, they were in collaboration with and assisted by

the civilian and military police whenever they recruited "comfort women".

この文書では、陸軍省は、北支那方面軍と中支那方面軍の職員長に、遠征軍が 「コンフォートステ

ーションで働く女性」 の採用を管理し、採用担当者を注意深く精査し、調整するように指定されているこ

とを通知しました。

そのような募集については、地元の民間および憲兵と緊密に協力している(吉見編、1995:105-

106)。

したがって、採用担当者は 「慰安婦」 を採用するために独立して活動することはありませんでした。

彼らは軍によって精査され、選ばれる必要がありました。

したがって、「慰安婦」 を採用するときは常に、民間および憲兵と協力して支援しました。

4-2 Kidnapping by Korean recruiters and the military/Governor-General

4-2韓国のリクルーターと軍/総督による誘拐

As for Ramseyer's description of kidnapping by recruiters in Korea (p.5), it is certainly true that

unscrupulous recruiters engaged in human trafficking and kidnapping.

But when recruitment for military "comfort women", as distinguished from women forced to work

at private brothels,involved such tactics, and when kidnapped women were forced into military

comfort stations,Ramseyer's argument that "It was not that the government?either the Korean or

the Japanese government?forced women into prostitution. It was not that the Japanese army

worked with fraudulent recruiters. It was not even that recruiters focused on the army's comfort

stations",surely collapses.

I would like to consider this point below.

ラムザイアーによる韓国のリクルーターによる誘拐の説明(p.5)については、悪意のあるリクルーター

が人身売買や誘拐に従事したことは確かに真実です。

しかし、民間の売春婦で働くことを余儀なくされた女性とは異なり、軍の「慰安婦」の募集がそのような

戦術を含んだとき、そして誘拐された女性が軍の慰安所に強制されたとき、ラムゼイヤーの主張は 「

政府でも韓国人でもなかったまたは日本政府は女性を売春に追いやった。 日本軍が不正な徴兵者と

協力したのではなく、軍の慰安所に焦点を合わせた徴兵者でさえなかった 」 と確かに崩壊する。

この点を以下で考察したいと思います。

When the military recruited "comfort women" in Korea, the actual recruitment was done by

private contractors selected by the military or the police, under the direction of the civilian and

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4029325 military police (see 4-1 above).

If the recruitment involved kidnapping or human trafficking, the Korea Army (Japanese Army

stationed in Korea) or the police under the Office of Governor-General would definitely have

noticed. If the Governor-General issued travel permits for women who were victims of human

trafficking or kidnapping, that would indicate the culpability of the Governor-General’s office.

軍が韓国で 「慰安婦」 を募集したとき、実際の募集は、https://ssrn.com/abstract=4029325で 入手

可能な民間および電子コピーの指示の下で、軍または警察によって選択された民間請負業者によって

行われました。

憲兵(上記4-1を参照)。

誘拐や人身売買が行われた場合、韓国軍(韓国に駐留している日本軍)や総督府の警察は間違い

なく気づいたでしょう。総督が人身売買や誘拐の被害者である女性に旅行許可証を発行した場合、そ

れは総督府の責任を示します。

Further, the Korea Army and contractors worked closely to transport "comfort women".

For example, a SEATIC (South East Asia Translation and Interrogation Center)10 document

states as follows (SEATIC, 1944:10):

さらに、韓国軍と請負業者は 「慰安婦」 の輸送に緊密に協力しました。

たとえば、SEATIC(東南アジア翻訳および尋問センター)10の文書には、次のように記載されていま

す(SEATIC、1944:10)。

M.739[Comfort station manager], his wife and sister-in-law made some money as restaurant

keepers in Keijo, Korea, but [with] their trade declining they looked for an opportunity to make more

money and applied to Army H.Q. in Keijo for permission to take "comfort girls" from Korea to

Burma. [...]

H.Q. Korea Army gave him a letter addressed to all military H.Q. of the Japanese Army,requesting

them to furnish any assistance he might require, transport, rations, medical attention etc.

M.739 [コンフォートステーションマネージャー]、彼の妻と義理の姉は韓国の慶應でレストランの番人

としてお金を稼いだが、彼らの貿易は衰退し、より多くのお金を稼ぐ機会を探して陸軍本部に申請し

た。

H.Q.韓国軍は彼にすべての軍事本部に宛てた手紙を与えた。日本軍の、彼が必要とするかもしれな

い援助、輸送、配給、医療などを提供するように彼らに要求する。

As stated, the Korea Army was requesting every unit of the military to provide "any assistance"

to the recruiter/comfort station manager in order to transport "comfort women".

The same document also shows that the military provided the contractors with funds for

transportation and medical expenses and sold them food from the military supply depot when they

opened comfort stations in Burma (SEATIC, 1944:11).

Thus, contractors were not entities operating independently from the military, but subservient to

the military, receiving various forms of assistance from the military and functioned in support of the

military.

述べたように、韓国軍は、「慰安婦」 を輸送するために、軍のすべての部隊に、リクルーター/慰安所

長に 「あらゆる援助」 を提供するように要求していました。

同じ文書はまた、軍が請負業者に輸送費と医療費の資金を提供し、ビルマに慰安所を開設したとき

に軍の補給所から食料を販売したことを示しています(SEATIC、1944:11)。

したがって、請負業者は軍隊から独立して活動する実体ではなく、軍隊に従属し、軍隊からさまざま

な形の支援を受け、軍隊を支援するために機能した。

Regarding the accountability of the expeditionary armies in the occupied areas that received "

comfort women", there were three types of military comfort stations: (i) comfort stations directly

operated by the military, (ii) comfort stations exclusively serving the military, and (iii) civilian

brothels in occupied areas that were temporarily designated by the military as comfort stations.

Comfort stations of the first two types are particularly problematic:

If women who were victims of human trafficking and kidnapping were forced to become "comfort

women" at comfort stations directly run by the military, the military should be considered most

culpable as the principal offender.

Comfort stations exclusively serving the military were operated by designated private contractors,

but the primary responsibility for allowing victims of human trafficking or kidnaping to be forced to

work at these comfort stations would still lie with the military, since the stations were regulated and

supervised by the military; buildings for the comfort stations were provided by the military, as were

food, clothing, and sanitary supplies including condoms; rules and prices were determined by the

military; and periodic exams for venereal disease were conducted by a military doctor or medic

(Yoshimi, 2000:133-138).

「慰安婦」 を受け入れた占領地の遠征軍の説明責任については、(i)軍が直接運営する慰安所、(ii)

軍専用の慰安所、(i)軍専用の慰安所の3種類があった。 iii)軍によって一時的に慰安所として指定さ

れた占領地の民間の売春婦。最初の2つのタイプの慰安所は特に問題があります。

人身売買や誘拐の被害者だった女性が、軍が直接運営する慰安婦で「慰安婦」になることを余儀なく

された場合、軍は主犯として最も責任があると見なされるべきである。

軍専用の慰安所は指定された民間請負業者によって運営されていましたが、人身売買や誘拐の被

害者がこれらの慰安所で働くことを強制されることを許可する主な責任は、軍にあります。軍隊;慰安所

の建物は軍によって提供され、食料、衣類、およびコンドームを含む衛生用品も同様でした。ルールと

価格は軍によって決定されました。性感染症の定期検査は、軍の医師または医療従事者によって実

施されました(Yoshimi、2000:133-138)。

Even in comfort stations in the third category, the military would be similarly culpable if such labor

took place while they were under military designation.

第3のカテゴリーの慰安所でも、軍の指定下にある間にそのような労働が行われた場合、軍は同様

に責任を問われることになります。

In fact, kidnapping of women as "comfort women" was exceedingly common, and yet the military

took no action when human trafficking or kidnapping occurred. Yamada Seikichi, a military logistics

officer (Second Lieutenant) overseeing comfort stations in Wuhan in 1943,wrote that the logistics

unit reviewed pictures of the "comfort women, their family registry papers, agreements, parental

consent forms, and police permits, and created personnel files recording the addresses and

occupation of their guardians and amounts of advances they received, but he did not recognize that

human trafficking for the purpose of transporting the victim overseas was against the law (Yamada,

1978:86).

In addition, even though he wrote that women from the Korean peninsula "did not have a history

[of prostitution] and tended to be young, around eighteen or nineteen" (Ibid.), he was not troubled

by these facts.

実際、「慰安婦」 としての女性の誘拐は非常に一般的でしたが、人身売買や誘拐が発生したとき、軍

は何の行動も取りませんでした。

1943年に武漢の慰安所を監督する兵站官(少尉)の山田誠吉は、「 慰安婦、その家族登録書類、協

定、親の同意書、警察の許可証 」 の写真を検討し、人員を作成したと書いた。

保護者の住所と職業、および彼らが受け取った前払金の金額を記録したファイルが、犠牲者を海外

に輸送する目的での人身売買が法律に違反していることを彼は認識していませんでした(山田、1978:

86)。

また、朝鮮半島の女性は 「 売春の歴史がなく、18歳か19歳くらいの若い傾向があった 」 と書いてい

たが(同上)、これらの事実に悩まされることはなかった。

Military doctor Nagasawa Kenichi who was examining "comfort women" for venereal disease at

the same Wuhan military logistics unit was assigned to examine a young woman who was brought

into the comfort station screaming and desperately resisting. "Crying, she protested".

I was told I would be consoling soldiers in places called comfort stations. ... I had no idea I'd be

doing this kind of thing in a place like this. I want to go home, please let me go home! 11

She could not be examined that day. The next day, the woman returned for the examination eyes

swollen with tears and shaking violently, which, Nagasawa surmised, indicated that she could not

refuse the work because she owed money for the cash advance and had been beaten in the face by

the comfort station operator (Nagasawa, 1983:147-148).

The woman was brought from Japan and had no prior history of prostitution, but she was

nonetheless forced to become a “comfort woman” in violation of Home Ministry policy. Indeed, it

was clear that she was the victim of human trafficking and kidnapping since she was deceptively

recruited and placed in debt bondage, but neither military officers or the military doctor recognized

that they were obliged to go after her recruiters and owner and liberate the woman.

This corroborates the fact that the military was the principal party responsible for permitting

human trafficking and kidnapping.

同じ武漢兵站部隊で「慰安婦」の性病を診察していた軍医長澤健一が、慰安婦に連れてこられて叫

び、必死に抵抗した若い女性を診察することになった。 「泣いて、彼女は抗議した」。

慰安所と呼ばれる場所で兵士を慰めると言われました。 …こんなところにこんなことをやろうとは思

っていませんでした。家に帰りたい、家に帰らせてください!11

その日彼女は診察できなかった。翌日、女性は涙で腫れ、激しく震えながら診察に戻ったが、長澤容

疑者は、キャッシングサービスのお金を借りていて、コンフォートステーションに殴打されていたため、

仕事を断ることができなかったと推測した。オペレーター(長澤、1983:147-148)。

この女性は日本から連れてこられ、売春歴はありませんでしたが、内務省の方針に違反して「慰安

婦」になることを余儀なくされました。確かに、彼女が人身売買と誘拐の犠牲者であったことは明らかで

したが、彼女は一見採用されて借金による束縛に置かれましたが、軍の将校も軍の医師も、彼女の採

用者と所有者を追いかけ、女性を解放する義務があることを認識していませんでした。

これは、軍隊が人身売買と誘拐を許可する責任を負う主要な当事者であったという事実を裏付けて

います。

There are numerous examples of Korean "comfort women" who meet the definition of victims of

human trafficking and kidnapping for the purpose of transporting overseas.

According to the testimony of Song Sin-do, who was forced into a comfort station in Wuchang in

1938, she was 16 when she left home because her parents were trying to force her into an

unwanted marriage.

While she was wandering in Daejeon, she was deceived by a middle-aged woman who told her, "If

you go to the war zone, you could work for the nation, or in any case you wouldn't have to get

married, so don’t worry" and handed her over to a Sinuiju broker, who then took her to Wuchang.

There, she was forcibly examined for venereal disease at a comfort station established by the

military unit named “Sekaikan" and then forced to sleep with the military doctor, which she fiercely

resisted.

She was punched and kicked by the broker, who pressed her, saying "You owe us money, so pay

us back if you want to leave".

When Song asked what the debt was about, she was told that it was for expenses such as food,

clothing, and train and boat fares from Korea to Wuchang.

She felt she could not refuse anymore (Nishino et al.ed., 2006:45-48).

She was never allowed to leave the comfort station until Japan's surrender.

This amounts to a violation of the law against kidnapping for the purpose of transporting victims

overseas, but the military did not pursue this crime.

There are many cases like this one where there were no advance payment contracts.

海外への輸送を目的とした人身売買や誘拐の被害者の定義を満たす韓国の 「慰安婦」 の例は数多

くあります。

1938年に武昌の慰安所??に強制収容された宋神道の証言によると、両親が望まない結婚を強要し

ようとして家を出たとき、彼女は16歳だった。

大田を徘徊していると、中年の女性に騙されて「戦争地帯に行けば、国のために働くことができるし、

とにかく結婚する必要がないので、」と言った。心配しないで」と彼女を新義州のブローカーに引き渡し、

新義州のブローカーは彼女をウーチャンに連れて行った。

そこで、軍部隊「世界観」が設置したコンフォートステーションで性感染症の検査を強要された後、軍

医と一緒に寝ることを余儀なくされ、激しく抵抗した。

彼女はブローカーに殴られて蹴られ、「あなたは私たちにお金を借りているので、去りたいのなら私た

ちに返済してください」と彼女に圧力をかけました。

宋氏が借金について尋ねたところ、韓国から武昌までの食料、衣類、電車や船の運賃などの費用が

かかると言われた。

彼女はもう断ることができないと感じた(Nishino et al。、2006:45-48)。

彼女は日本の降伏までコンフォートステーションを離れることを決して許されなかった。

これは、犠牲者を海外に移送する目的での誘拐を禁止する法律の違反に相当しますが、軍はこの犯

罪を追求しませんでした。

このように前払い契約がない場合が多いです。

Finally, Ramseyer cites a report by the U.S. Office of War Information, which interrogated twenty

Korean "comfort women" and two Japanese comfort station operators (p.6).

It states that the Japanese military had transported 703 "comfort women" from Korea to Burma

in 1942, and that they, believing recruiters' "false representations",” had received "an advance of a

few hundred yen" (U.S. Office of War Information, 1944:1).

According to the report, these "false representations" involved:

最後に、ラムザイヤーは、20人の韓国の 「慰安婦」 と2人の日本の慰安所運営者に尋問した米国戦

時情報局の報告を引用している(p.6)。

日本軍は1942年に703人の 「慰安婦」 を韓国からビルマに輸送し、彼らは採用担当者の 「虚偽の表

明」 を信じて 「数百円の前払い」 を受け取ったと述べている(1944:1)。

レポートによると、これらの 「誤った表現」 には以下が含まれます。

The nature of this "service" was not specified but it was assumed to be work connected with

visiting the wounded in hospitals, rolling bandages, and generally making the soldiers happy.

The inducement used by these agents was plenty of money, an opportunity to pay off the family

debts, easy work, and the prospect of a new life in a new land?Singapore.

この 「奉仕」 の性質は特定されていませんが、病院で負傷者を訪問し、包帯を巻いて、一般的に兵

士を幸せにすることに関連する仕事であると想定されていました。

これらのエージェントが使用した誘因は、たくさんのお金、家族の借金を返済する機会、簡単な仕事、

そして新しい土地、シンガポールでの新しい生活の見通しでした。

Ramseyer does not cite the above passage, but it clearly refers not to ordinary contractual

agreements but to criminal acts in violation of laws against kidnapping and human trafficking for the

purpose of transporting victims overseas.

According to another report documenting the interrogation of the same group of prisoners of war,

the twenty-two Korean "comfort women" (two had died before the women were captured by the U.

S.) were "purchased" for between 300 and 1,000 yen depending on their personality, looks, and age,

and became "the sole property" of the comfort station operators (SEATIC, 1944:10-11).

This further indicates that the women were not independent agents capable of entering into

contracts, but rather, kidnapping victims.

ラムザイヤーは上記の箇所を引用していませんが、それは明らかに通常の契約上の合意ではなく、

犠牲者を海外に輸送することを目的とした誘拐や人身売買に対する法律に違反する犯罪行為を指し

ます。

同じ捕虜グループの尋問を記録した別の報告によると、22人の韓国の「慰安婦」(2人は米国に捕虜

になる前に死亡した)は、300円から1,000円の間で 「購入」 された。

彼らの性格、外見、年齢は、慰安所の運営者の 「唯一の財産」 となった(SEATIC、1944:10-11)。

これはさらに、女性が契約を結ぶことができる独立した代理人ではなく、むしろ犠牲者を誘拐したこと

を示しています。

Another fact that eludes Ramseyer is that, according to the U.S. interrogation report of the

twenty Korean "comfort women", they arrived in Rangoon on or around August 20, 1942 and were

detained by the U.S. forces on August 10, 1944 (U.S. Office of War Information, 1944:1-2),indicating

either that their contractual terms were longer than six months to one year, or that they were not

released even after the expiration of the term, contrary to Ramseyer's claim that women returned

home after one year to two years.

ラムゼイヤーを逃れるもう一つの事実は、20人の韓国の 「慰安婦」 の米国の尋問報告によると、彼

らは1942年8月20日頃にラングーンに到着し、1944年8月10日に米軍によって拘留されたということで

す。(戦争情報、1944:1-2)、慰安婦が1年後に帰国したというラムゼイヤーの主張に反して、契約期間

が6か月から1年より長いか、期間満了後も解放されなかったことを示しています。 2年に。

4-3 The purposes for establishing comfort stations and the principal party behind their

establishment

4-3 慰安所を設立する目的とその設立の背後にある主要な当事者

Ramseyer argues that the purpose for establishing comfort stations was the prevention of rape by

soldiers and the spread of venereal disease, particularly emphasizing the latter (p.5), but this is

inaccurate.

The primary purpose of setting up comfort stations was to maintain soldiers' morale and reduce

their dissatisfaction through the provision of sexual "comfort"; the second was to prevent rape by

the soldiers; the third, to forestall the outbreak of venereal disease; and the fourth, to prevent

espionage (i.e., by preventing military personnel from disclosing military secrets at private brothels)

(Yoshimi, 2000:65-75).

Indeed, Ramseyer’s argument cannot explain why comfort stations were set up even in remote

areas near the front line that had been evacuated, with no residents or private brothels nearby.

The overarching reason for establishing comfort stations was that the military had determined

that it needed to provide sexual comfort to soldiers in order to keep their discontent from exploding.

ラムザイヤーは、慰安所を設立する目的は、兵士によるレイプの防止と性感染症の蔓延であると主

張し、特に性感染症を強調しているが(p.5)、これは不正確である。

慰安所を設置する主な目的は、兵士の士気を維持し、性的な「慰安」を提供することで兵士の不満を

減らすことでした。 2つ目は、兵士によるレイプを防ぐことでした。第三に、性病の発生を未然に防ぐた

め。そして第四に、スパイ行為を防ぐために(すなわち、軍人が私的な売春宿で軍の秘密を開示する

のを防ぐことによって)(吉見、2000:65-75)。

確かに、ラムザイヤーの主張は、避難した最前線の近くの遠隔地にさえ、近くに居住者や売春宿が

なく、慰安所が設置された理由を説明することはできません。

慰安所を設立する最も重要な理由は、軍隊が兵士の不満が爆発するのを防ぐために兵士に性的な

慰安を提供する必要があると判断したことでした。

Ramseyer’s claim that there were plenty of prostitutes that followed the military (p.5) is also

untrue.

The Japanese military stringently restricted civilians from entering war zones, and camp followers,

including prostitutes other than military "comfort women",could not come near a military

encampment.

For example, when the Japanese military occupied Hankow in 1938,representatives of the Army,

the Navy, and the Consul-General in Shanghai had decided in advance that the transport of

Japanese civilians to Hankow other than residents of the concession would be prohibited until

capacity was restored, with the exception of those moving to Hankow for the purpose of "opening

military comfort stations" (Yoshimi ed., 1992:115-116).

Further, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs severely restricted travelers to China, issuing a directive

on May 7, 1940 that prohibited anyone except for consolatory visitors approved by the Army or the

Navy, housekeepers, people traveling for trade, and employees of trading companies in China (ibid.,

123-24).

軍隊に続いた売春婦がたくさんいたというラムザイヤーの主張(p.5)も真実ではありません。

日本軍は民間人の戦争地帯への立ち入りを厳しく制限し、軍の 「慰安婦」 以外の売春婦を含む非

戦闘従軍者は軍の野営地に近づくことができなかった。

たとえば、1938年に日本軍が漢口を占領したとき、陸軍、海軍、上海総領事館の代表は、譲歩の居

住者以外の日本人民間人の漢口への輸送を定員まで禁止することを事前に決定しました。

「軍の慰安所を開く」 目的で漢口に移動した者を除いて、復元された(吉見編、1992:115-116)。

さらに、外務省は中国への旅行者を厳しく制限し、1940年5月7日に、陸軍または海軍によって承認さ

れた慰めの訪問者、家政婦、貿易のために旅行する人々、および中国の商社の従業員を除くすべて

の人を禁止する指令を出しました (同上、123-24)。

Of course, it goes without saying that there would have been no recruitment for "comfort women"

unless the military had decided to establish comfort stations.

After the decision to establish the comfort stations, the military vetted and selected contractors

to recruit "comfort women", and as such the initiative for the deployment of "comfort women" was

always with the military.

For example, on December 11th, 1937, days before the Japanese occupation of Nanking, Iinuma

Mamoru, the Chief of Staff of the Shanghai Expeditionary Force, wrote in his diary: "I received

documents from the [Central China] Area Army regarding the [establishment of a] comfort station.

I shall implement it", (Nankinsenshi henshu iinkai ed., 1989:211); on June 27th, 1938, Okabe

Naosabur?, the Chief of Staff of the North China Area Army likewise ordered the "establishment of

a facility for sexual comfort as quickly as possible" (Yoshimi ed.,1992:210).

もちろん、軍が慰安所を設置することを決定しなければ、「慰安婦」 の採用はなかったことは言うまで

もありません。

慰安婦の設置が決定された後、軍は 「慰安婦」 を採用するために請負業者を精査し、選択しまし

た。

そのため、「慰安婦」 の配備のイニシアチブは常に軍にありました。

たとえば、1937年12月11日、日本が南京を占領する数日前に、上海遠征軍の参謀長である飯沼守

は日記に次のように書いています。

「 コンフォートステーションの設置。 私はそれを実行します 」(南京県参謀飯沼編、1989:211)。

1938年6月27日、北支那方面軍参謀長の岡部直三郎も同様に 「 できるだけ早く性的慰めの施設を

設立する 」 ことを命じた (吉見編、1992:210)。

4-4 Contract duration and income

4-4 契約期間と収入

Ramseyer argues that (i) the contract duration for "comfort women" in Burma was six months to

one year, much shorter than the six years for licensed prostitutes in Japan and three years for

licensed prostitutes in Korea, and (ii) “comfort women” had higher incomes than prostitutes in

Tokyo (p.6), but is there evidence to back up such claims?

ラムザイヤーは、(i)ビルマの「慰安婦」の契約期間は6か月から1年であり、日本の売春婦の6年、韓

国の売春婦の3年よりもはるかに短かった、(ii)「慰安婦」と主張している。 」は東京の売春婦よりも収

入が多かった(p.6)が、そのような主張を裏付ける証拠はあるのだろうか?

As for claim (i), Ramseyer cites the collection of official documents compiled by the Asia Women’s

Fund (Josei no tame no Ajia heiwa kokumin kikin ed., 1997: v1, 19), but there is no such account in

that collection.

The U.S. report mentioned above documenting the Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/

abstract=4029325 13 interrogations of twenty "comfort women" and their house masters detained

in Myitkyina,Burma, does indeed state that the contract duration for the Korean "comfort women"

ranged from six months to a year, but these women had been in Burma for two years by the time

they were detained by the U.S. military as previously mentioned (U.S. Office of War Information,1944:

1).

In any case, this is but one specific comfort station.

As for claim (ii), Ramseyer argues that "comfort women" earned 600 to 700 yen in just two years

while licensed prostitutes in Japan only earned 1,000 to 1,200 yen over six years (p.6), but these

figures are based on flimsy evidence.

He is generalizing from the aforementioned documented case in which Kobe-based brothel owner ?

uchi T?shichi recruited “comfort women” to work at the comfort station serving the military unit

dispatched to Shanghai in late 1937 to early 1938 for two-year term with the promised advance of

500-1,000 yen, and actually paid two women 642 yen and 691 yen respectively (Naimusho

keihokyokucho, 1938).

But these contract terms and amount of advance from a single case cannot be generalized to all

Japanese "comfort women".

Further, it is questionable whether advances paid for licensed prostitutes in 1925 make for

appropriate comparison with those paid for "comfort women" after 1937.

クレーム(i)については、ラムザイヤーはアジア女性基金がまとめた公式文書のコレクションを引用し

ているが(女性の飼いののアジア平和国民紀金編、1997:v1、19)、そのコレクションにはそのような記

述はない。

https://ssrn.com/abstract=4029325 で入手可能な電子コピーを文書化した上記の米国の報告書ビ

ルマのミッチーナーに拘留された20人の「慰安婦」とその家長の13の尋問は確かに韓国の「慰安婦」は

6か月から1年の範囲でしたが、前述のように、これらの女性は米軍に拘束されるまでに2年間ビルマに

滞在していました(US Office of War Information、1944:1)。

いずれにせよ、これは1つの特定のコンフォートステーションにすぎません。

クレーム(ii)については、ラムザイアーは 「慰安婦」 はたった2年で600〜700円稼いだが、日本の売

春婦は6年間で1,000〜1200円しか稼げなかったと主張しているが(p.6)、これらの数字は薄っぺらなも

のに基づいている。証拠。

彼は、神戸を拠点とする売春宿のオーナーである大内東七が「快適さ」を募集した前述の文書化され

た事例から一般化しています。

1937年後半から1938年初頭に上海に派遣された軍部隊に仕えるコンフォートステーションで働く女性

たち」は、500〜1,000円の前払いを約束し、実際に2人の女性にそれぞれ642円と691円を支払った(内

武商会法廷町、1938)。

しかし、これらの契約条件と単一の訴訟からの前払い額は、すべての日本人の「慰安婦」に一般化す

ることはできません。

さらに、1925年に認可された売春婦に支払われた前払金が、1937年以降に「慰安婦」に支払われた

前払金と適切に比較できるかどうかは疑わしい。

An even larger problem for Ramseyer is that the advances and contract duration he is comparing

were not agreements between the brothel owner/manager and the women themselves, but de facto

between the owner/manager and the women's relatives or their current holders, and as such they

were contracts for the sale and purchase of the women, thatis, provisions pertaining to the slave

trade. Advance payments were typically made to the relatives, intermediaries, and/or current

holders of the women and not to the women themselves.

Since Ramseyer does not consider how much owners actually paid women, we have no way of

knowing their income.

ラムゼイヤーにとってさらに大きな問題は、彼が比較している前払金と契約期間が、奴隷の所有者/

管理者と女性自身の間の合意ではなく、事実上、所有者/管理者と女性の親戚または彼らの現在の所

有者の間の合意であったことです。それらは女性の売買の契約、つまり奴隷貿易に関連する条項でし

た。前払いは通常、女性自身ではなく、女性の親戚、仲介者、および/または現在の保有者に支払わ

れました。

ラムザイヤーは、所有者が実際に女性に支払った金額を考慮していないため、女性の収入を知る方

法がありません。

4-5 Conditions for exiting the trade

4-5 取引を終了するための条件

Ramseyer asserts that (i) "comfort women" could return after the expiration of their contract or

repayment of the advance in its entirety, and (ii) even if they owed 1,000 yen, if they could pay off

all their debts within a few months they could return to their countries (p.6).

Let us examine the evidence.

ラムザイヤーは、(i)「慰安婦」は、契約満了または前払金の全額返済後に返還できる、(ii)1,000円

の借金があっても、数か月以内に全額返済できれば、返済できると主張している。彼らは自国に戻る

ことができた(p.6)。

証拠を調べてみましょう。

Ramseyer identifies the source of the first claim as the diary of a Korean employee who worked

at comfort stations but does not specify where in the diary he found the reference. In actuality,

there were three conditions that had to be satisfied before "comfort women" under advance

payment contracts could leave comfort stations:

1) full payment of all advances and any additional debts or expiration of the contract;

2) permission of the comfort station operator;

and 3) permission of the military. For example, the July 9, 1944 entry of the diary of the comfort

station employee documents that the Kanemoto sisters, who were "comfort women", "decided to

stop working to return home, and their master Nishihara approved, so I submitted paperwork for

them to retire" (An ed., 2013:365).

This indicates that approval by the comfort station operator was required. Similarly, Article 13 of

the Regulation for the Operation of Comfort Facilities and Lodging Accommodations (December 11,

1943) of the Military Administration of Malaya stipulated that "operators and working women that

close the business or retire shall petition the Governor in the corresponding region and receive

permission" (Josei no tame no Ajia heiwa kokumin kikin ed., 1997, v3:27).

Thus, these three conditions had to be met in order for women to be freed from the comfort

station.

ラムザイヤーは、

(i)「慰安婦」は契約満了後または前払金の返済後に返還される可能性があると主張している。

日記で彼は参照を見つけました。

実際には、前払い契約に基づく 「慰安婦」 が慰安所を離れる前に満たされなければならない3つ

の条件がありました。

1) すべての前払金および追加の債務の全額支払いまたは契約の満了。

2) コンフォートステーションオペレーターの許可。

3) 軍の許可。

例えば、1944年7月9日の慰安婦日記の記入では、「慰安婦」 であった金本姉妹が

「帰国することをやめ、主人の西原が承認した」 との書類を提出しました。

彼らは引退する」(編、2013:365)。

これは、コンフォートステーションのオペレーターによる承認が必要であることを示しています。

同様に、マラヤ軍事政権の快適施設および宿泊施設の運営に関する規則(1943年12月11日)の第

13条は、「事業を閉鎖または退職する運営者および働く女性は、対応する地域の知事に請願し、許可

を得る」(上生の飼いならのアジア平和国民紀金編、1997年、v3:27)。

したがって、女性がコンフォートステーションから解放されるためには、これら3つの条件が満たされな

ければなりませんでした。

In fact, there were cases in which the military, citing war conditions, did not allow women to return

home even after paying back all their debts (SEATIC, 1944:11).

The diary of the comfort station employee (July 29, 1943) also documents the case of two "

comfort women" in Burma who tried to retire in July but ended up returning to Kinsenkan comfort

station,"because of an order pertaining to current military logistics" (An ed., 2013:281-282).

実際、軍隊は、戦争の状況を理由に、すべての借金を返済した後でも女性が家に帰ることを許可し

なかった場合がありました(SEATIC、1944:11)。

慰安所職員の日記(1943年7月29日)には、ビルマで7月に引退を試みたが、現在の兵站に関する命

令のために金泉館慰安所に戻った2人の 「慰安婦」 の事件も記録されている (編、2013:281-282)。

On the other hand, those without an advance payment contract like Song Sin-do were perpetually

detained.

She returned from China to Japan in 1946 after Japan's surrender, but was never able to return

to her homeland of Korea. Many women, including Wan Aihua from Shanxi Province, China; Huang

Youliang from Hainan Island, China; Maria Rosa Henson from the Philippines; and Jan Ruff O'Herne

from Semarang, Java, who were brutally captured by the military or the police did not sign any

contract, and did not know when they might be free again.

一方、宋神道のように前払い契約を結んでいない者は永久に拘留された。

彼女は日本の降伏後の1946年に中国から日本に戻ったが、故郷の韓国に戻ることはできなかった。

中国山西省のWanAihuaを含む多くの女性。中国海南島出身のHuangYouliang;フィリピン出身のマリア・

ローザ・ヘンソン。ジャワ島スマランのジャン・ラフ・オヘルネは、軍や警察に残酷に捕らえられ、契約に

署名せず、いつ再び解放されるかわかりませんでした。

Ramseyer bases his second claim on Senda Kako’s book, but the testimony in question is part of

the self-serving rationalization of a zegen (recruiter), who engaged in deception and human

trafficking on a regular basis, stressing that the conditions for "comfort women" were "not all that

bad" (Senda, 1973:26) and cannot be considered a source of accurate information.

ラムザイヤーは千田夏光の本に基づいて2番目の主張をしているが、問題の証言は、定期的に欺瞞

と人身売買に従事しているゼゲン(リクルーター)の自己奉仕的な合理化の一部であり、「慰安婦」の条

件を強調している「「それほど悪くはなかった」(Senda、1973:26)ので、正確な情報源とは見なされませ

ん。

As these analyses show, Ramseyer fails to consider the actual conditions under which women

were placed at comfort stations.

The women had to live in small rooms inside the comfort station where they also sexually serviced

officers and soldiers, and hence did not have the freedom to choose their residence. According to

comfort station regulations defined by the military, "comfort women" were either prohibited from

leaving the premises, or had to receive permission from the military to do so.

The same rules did not allow them freedom to exit, and they could not stop working unless the

above three conditions were met, even with a contract.

They did not have the right to refuse sexual relations with officers and soldiers.

And they were required to submit to periodic checkups for venereal disease.

Therefore, we must conclude that the comfort station system was a system of sexual slavery

established, regulated, and operated by the military (Yoshimi, 2000:139-151; Yoshimi, 2010:44-45).

Ignoring this reality, Ramseyer's argument, which presumes contracts freely negotiated and

entered into by contractors and "comfort women", can only exist in the realm of fantasy.

これらの分析が示すように、ラムザイヤーは女性が慰安所に配置された実際の条件を考慮していま

せん。

女性たちはコンフォートステーション内の小さな部屋に住む必要があり、そこでは将校や兵士にも性

的サービスを提供していました。そのため、住居を選択する自由がありませんでした。軍によって定義

された慰安所の規則によると、「慰安婦」は敷地を離れることを禁じられているか、軍から許可を受け

なければなりませんでした。

同じ規則では、彼らは自由に退出することができず、契約があっても、上記の3つの条件が満たされ

ない限り、彼らは仕事をやめることができませんでした。

彼らには、将校や兵士との性的関係を拒否する権利がありませんでした。

そして、彼らは性病の定期健康診断を受ける必要がありました。

したがって、コンフォートステーションシステムは、軍によって確立され、規制され、運営されている性

的奴隷制のシステムであると結論付けなければなりません(Yoshimi、2000:139-151; Yoshimi、2010:44

-45)。

この現実を無視すると、請負業者と「慰安婦」によって自由に交渉され締結された契約を前提とする

ラムザイヤーの議論は、ファンタジーの領域にのみ存在することができます。

4-6 High-earning "comfort women"

4-6 高収入の「慰安婦」

Ramseyer argues that "many brothel owners did indeed pay their prostitutes beyond that large up

-front advance",citing the comfort station employee's diary, as well as the testimony of Mun Oku-ju

(p.6).

Ramseyer also tells us “of all the Korean comfort women who left accounts, Mun Ok-ju seems to

have done well most flamboyantly.

Mun indeed had a postal banking passbook12, but it is unknown what percentage of "comfort

women" were able to have postal passbooks. Further, these passbooks were issued by the military

field force postal service,

so if "comfort women" had passbooks and used them to send money, that indicates, contrary to

Ramseyer's claim, that these women were not simply prostitutes working for independent brothels,

but had a status comparable to civilian workers of the military. Indeed, Jitsumoto Hirotsugu, who

was chief of the welfare bureau of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, testified in the Society and

Labor Committee of the House of Representatives in 1968, that while there was no direct

employment relationship between the military and "comfort women","they needed to have some

kind of status for the military to extend to them the use of [military] facilities, accommodations, and

other benefits, so they granted them the status of unpaid civilian workers [of the military] in order

to provide accommodations and other benefits" (Shugiin, 1968:7).

ラムザイヤーは、「多くの売春宿の所有者は、実際にその大規模な前払い金を超えて売春婦に支払

いをした」 と主張し、コンフォートステーションの従業員の日記と模擬国連の証言を引用している(p.6)。

ラムザイヤーはまた、「アカウントを残したすべての韓国の慰安婦の中で、ムン・オクジュは最も派手

にうまくやっていたようです。

ムンは確かに郵便通帳を持っていた12が、「慰安婦」 の何パーセントが郵便通帳を持っていたのか

は不明である。

さらに、これらのパスブックは軍の郵便局によって発行されたため、

「慰安婦」 が貯金通帳を持っていて送金に使用した場合、ラムザイヤーの主張に反して、

これらの女性は単に独立した売春宿で働く売春婦ではなかったことを示しています。

軍の民間労働者に匹敵する地位を持っていた。

確かに、厚生省福祉局長の実本博嗣氏は、1968年に衆議院社会労働委員会で、

軍と 「慰安婦」 との直接的な雇用関係はなかったと証言した。

彼らは、軍が [軍の] 施設、宿泊施設、およびその他の利益の使用を拡大するために

何らかの地位を持っている必要があったので、

彼らは彼らに [軍の] 無給の民間労働者の地位を与えました。

宿泊施設やその他の利益を提供する (Sh?giin、1968:7)。

Ramseyer quotes the testimony of Mun Oku-ju not from her published memoir, but from a right-

wing Korean website.

In it, she is said to have saved up a lot of money and sent 1,000 yen (when 1 rupee = 1 yen) to

her mother.

It describes how she went shopping in Rangoon and bought a diamond, making it appear as if she

was highly paid by the brothel.

ラムザイヤーは、公開された回想録からではなく、韓国の右翼のウェブサイトから、模擬国連の証言

を引用している。

その中で、彼女はたくさんのお金を貯め、1,000円(1ルピー= 1円の場合)を母親に送ったと言われて

います。

彼女がどのようにしてラングーンで買い物に行き、ダイヤモンドを購入したかを説明し、まるで売春宿

から高額の支払いを受けたかのように見せます。

This is far from the truth. In fact, Ramseyer himself quotes Mun stating "I saved a considerable

amount of money from tips",but fails to grasp how the vast majority of her savings came from

customer tips and not from the salary paid by the comfort station. In her memoir, she wrote "

Matsumoto (her owner) only took tickets from us and didn"t pay us".

Only when the women went on strike did "he pay us a pittance, like one or two yen".

It was after the "small tips from members of the military piled up into quite a sum" that she got a

postal savings passbook (Mun and Morikawa, 1996:75-76).

これは真実からほど遠いです。

実際、ラムザイヤー自身はムンが 「チップからかなりの金額を節約した」 と述べていますが、彼女の

節約の大部分がコンフォートステーションによって支払われた給与からではなく顧客のチップからどの

ようにもたらされたかを理解できていません。

彼女の回想録には、

「 松本(彼女の所有者)は私たちからチケットを受け取っただけで、

私たちにお金を払わなかった 」

と書いています。

女性たちがストライキをしたときだけ、

「 彼は私たちに1、2円のようなちょっとしたお金を払ってくれた 」

のです。

彼女が郵便貯金通帳を手に入れたのは、

「 軍人からの小さな助言がかなりの額に積み上げられた 」

後だった(Mun and Morikawa、1996:75-76)。

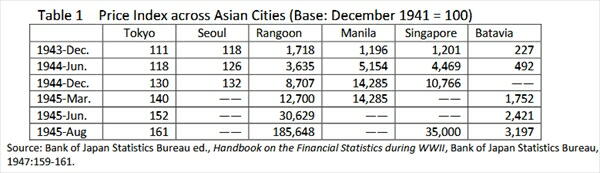

To understand how Mun was able to accumulate so much money in tips, we must also pay

attention to the fact that Burma was experiencing hyperinflation at the time (see table 1).

Ota Tsunezo, a scholar of Burmese history, explains how "worsening war conditions from the

second half of 1944 caused the value of military scrips (legal tender) issued by the military to

plummet, making them essentially worthless after the fall of Mandalay in March of 1945" (Ota,1967:

440).

According to the original postal savings data preserved in Japan, Mun first deposited 500 yen in

March 1943, and saved 25,742 yen by September 1945. She began saving money in 1943 when

inflation began to escalate, and the vast majority of the deposits, 20,860 yen, were made after April

1945, when the value of military scrips became practically nil (Mun and Morikawa, 1996:206).

Members and employees of the military lavishly tipped Mun with the scrips because they were

worthless otherwise.

ムンがどのようにしてチップにこれほど多くのお金を貯めることができたかを理解するには、ビルマが

当時ハイパーインフレーションを経験していたという事実にも注意を払う必要があります(表1を参照)。

ビルマの歴史学者である大田鶴蔵は、「1944年後半からの戦争状況の悪化により、軍が発行した法

定通貨の価値が急落し、1945年3月のマンダレーの崩壊後、彼らは本質的に無価値になりました」(?

ta、1967:440)。

日本で保存された元の郵便貯金データによると、ムンは1943年3月に最初に500円を預金し、1945年

9月までに25,742円を節約しました。彼女はインフレがエスカレートし始めた1943年にお金を節約し始め

ました。は、1945年4月に軍用スクリップの価値が実質的にゼロになった後に作成されました(Mun

and Morikawa、1996:206)。

軍のメンバーと従業員は、他の方法では価値がなかったので、ムンにスクリップを惜しみなく傾けまし

た。

Mun had saved 4,251 yen by the end of 1943, which was equivalent to about 292.0 yen in Seoul

(see table 1).

By the end of 1944 this amounted to 4,461 yen, which translated into approximately 67.6 yen in

Seoul.

There is no price index data for Seoul in 1945, but her savings of 25,142 yen in June 1945 was

worth 124.8 yen in Tokyo.

The amount in her account was still 25,142 yen in August 1945, but by then its value in Tokyo

plunged to 21.8 yen.

Withdrawals could not be made in Korea after Japan’s defeat, and even if she had been in Japan,

the value of her savings would have been minuscule because of post-war hyperinflation.

ムンは1943年末までに4,251円を節約しました。これはソウルの約292.0円に相当します(表1を参

照)。

1944年末までに4,461円になり、ソウルでは約67.6円になります。

1945年のソウルの物価指数データはありませんが、1945年6月の彼女の25,142円の節約は東京で

124.8円の価値がありました。

彼女の口座の金額は1945年8月にはまだ25,142円でしたが、それまでに東京での金額は21.8円に急

落しました。

日本の敗北後、韓国では撤退することができず、たとえ彼女が日本にいたとしても、戦後のハイパー

インフレーションのために彼女の貯蓄の価値はごくわずかだったでしょう。

Nevertheless, it is reasonable to wonder if, had she been able to return to Korea before the end of

the war, she might have withdrawn her considerable savings.

But this was not the case: the Japanese government had put in place conversion rates and

restrictions on withdrawals to prevent such withdrawals, lest hyperinflation in the occupied areas

spread to mainland Japan and Korea.

Hori Kazuo, professor emeritus of Kyoto University, who studies history of Asian economies writes

それでも、終戦前に韓国に帰国できたのなら、かなりの貯金を取り下げたのではないかと考えるのは

当然だ。

しかし、そうではありませんでした。日本政府は、占領地域のハイパーインフレーションが日本本土と

韓国に広がるのを防ぐために、そのような撤退を防ぐために転換率と撤退の制限を設けました。

アジア経済の歴史を研究している京都大学名誉教授の堀和生氏は次のように書いています。

Faced with this situation, the bureaucrats of the Ministry of Finance designed various creative

policies to prevent the influx of inflated funds to the domestic economy.

Policies intended to shut out funds from the occupied territories, such as limits to remittances,

compulsory deposits in local accounts, imposition of a percentage fee on remittance conversion, and

freezing of savings, were implemented one after another.(Hori, 2015, 17)

このような状況に直面して、財務省の官僚は、国内経済への膨らんだ資金の流入を防ぐために、さ

まざまな創造的な政策を立案しました。

送金の制限、地方口座への強制預金、送金転換へのパーセンテージ手数料の賦課、貯蓄の凍結な

ど、占領地からの資金を締め出すことを目的とした政策が次々と実施された(堀、2015、17)。

"Freezing of savings" here means that funds transferred from overseas were divided into two

accounts, one in a foreign denomination and the other in Japanese yen (in Japan and Korea), and

withdrawals from the foreign denominated account were severely restricted. Therefore, it was

impossible to withdraw hyperinflated rupees as yen in Japan or Korea without drastically diminishing

their value.

ここでいう 「貯蓄の凍結」 とは、海外から送金する資金を外貨と日本円(日本・韓国)の2つの口座に

分け、外貨口座からの引き出しを厳しく制限したことを意味します。そのため、日本や韓国では、ハイ

パーインフレーションのルピーを大幅に値下げせずに円で引き下げることはできませんでした。

In his diary on December 4, 1944, the comfort station employee wrote that he transferred 11,000

yen on behalf of a "comfort woman" retired in Singapore named Kim (An ed.,2013:398).

This amount was equivalent to 134.9 yen in Seoul, which is chump change considering that it

represented the earnings for two years of sexual servitude under captivity (about 5.6 yen per

month).

It also cannot be assumed that she could convert and withdraw 11,000 yen: even when “comfort

women” saved up inflated military scrips under hyperinflation and transferred them home, "amount

in excess of standard living expenses could not be Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/

abstract=4029325 17 withdrawn due to the restriction and freezing of funds transferred from

overseas" (Hori,2015:19).

1944年12月4日の日記で、慰安所職員は、シンガポールで引退したキムという「慰安婦」に代わって

11,000円を送金したと書いている(An ed。、2013:398)。

この金額はソウルで134.9円に相当し、捕われの身での2年間の性的奴隷制の収入(月額約5.6円)を

考えると大きな変化です。

また、彼女が11,000円を転用して引き出すことができるとは限りません。

「慰安婦」 がハイパーインフレーションで膨らんだ軍用スクリップを保存して家に持ち帰ったとしても、

「標準的な生活費を超える金額は、https://ssrn.com/abstract=4029325 17 海外からの送金の制限と

凍結により撤回」(堀、2015:19)。

Therefore, Ramseyer's argument that "comfort women" were exceedingly well-paid, as brothel

operators "needed to promise pay substantially higher even than the Tokyo and Seoul brothels" (p.

1) is contrary to fact.

したがって、売春宿の運営者は「東京やソウルの売春宿よりもかなり高い賃金を約束する必要があ

る」(p.1)ため、「慰安婦」は非常に高給であるというラムザイヤーの主張は事実に反している。

5. Conclusions

5。結論

Ramseyer argues that the contract between contractors and "comfort women" followed the

principles of "credible commitments" in game theory. According to his analysis, contractors and "

comfort women" each advocated for their interest, which led to the contract stipulating the

payment of large advances and two-year terms, and, at least before the last months of the war,"

comfort women" returning home after either serving their contract terms or paying off their debt

early (p.7).

ラムザイヤーは、請負業者と 「慰安婦」 の間の契約は、ゲーム理論における 「信頼できるコミットメ

ント」 の原則に従っていると主張しています。彼の分析によると、請負業者と 「慰安婦」 はそれぞれ彼

らの利益を主張し、それは多額の前払いと2年の任期の支払いを規定する契約につながり、少なくとも

戦争の最後の数ヶ月前には 「慰安婦」 でした。

契約条件を満たした後、または債務を早期に返済した後、帰国する(p.7)。

But Ramseyer is ignoring many important facts in making such assertions. First of all, (i) the

military and government established and maintained the system of sexual slavery called the "

comfort women" system, in which contractors were not autonomous, but agents of the military.

The contractors could not even determine the fees they charged at their comfort stations. Next,

(ii) even when contracts were signed, "comfort women" were not the primary party to the contract:

contracts were negotiated between the contractor and the woman's family members in the case of

women who were not prostitutes, and between the current master and new master for existing

prostitutes.

Moreover, (iii) it was only Japanese women for the most part, and some Korean women, who had

contracts to be "comfort women": many Korean, Chinese, Taiwanese, Filipina, Indonesian, Dutch,

East Timorean, and other women were trafficked or kidnapped by the military or its contractors and

imprisoned at comfort stations,without any contractual conditions for release. Finally, (iv) even with

a contract, there were many women who were unable to return home after their terms had expired

or all debts had been repaid.

As I have demonstrated in this article, there are many instances in Ramseyer's paper where he

fails to provide any evidence for the claims he makes, or the sources he presents actually prove

the opposite of what he claims, or, in some instances, he simply makes things up. As such, his paper

is utterly bankrupt and bears no resemblance to a scholarly work.

しかし、ラムザイヤーはそのような主張をする際に多くの重要な事実を無視しています。まず第一に、

(i)軍と政府は、請負業者が自律的ではなく軍の代理人である「慰安婦」制度と呼ばれる性的奴隷制度

を確立し維持した。